George Benjamin: Written on Skin

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden. 13 January 2017

Since it premiered in 2012, Written on Skin, George Benjamin’s first full-length opera (to a text by Martin Creed), has been hailed as one of the masterpieces of the contemporary opera world, bringing such accolades as “the work of a genius  unleashed”. This 90 minute work was composed over two years of concentration and virtual isolation, while Benjamin eschewed all other composition, teaching, and conducting work. It was commissioned by the Festival d’Aix-en-Provence, along with the Royal Opera House and opera houses in Amsterdam, Toulouse, and Florence. A request to base the opera on something related to the Occitan area of Provence led to a mediaeval tale about a troubadour employed by a local lord who has a love affair with the lord’s wife. When he finds out, the lord kills the troubadour, cooks his heart and feeds it to his wife. When she finds out what she has eaten, she swears to never eat or drink again to keep her lover’s taste in her mouth. She avoids the lord’s anger and his sword by leaping from a window to her death. Continue reading

unleashed”. This 90 minute work was composed over two years of concentration and virtual isolation, while Benjamin eschewed all other composition, teaching, and conducting work. It was commissioned by the Festival d’Aix-en-Provence, along with the Royal Opera House and opera houses in Amsterdam, Toulouse, and Florence. A request to base the opera on something related to the Occitan area of Provence led to a mediaeval tale about a troubadour employed by a local lord who has a love affair with the lord’s wife. When he finds out, the lord kills the troubadour, cooks his heart and feeds it to his wife. When she finds out what she has eaten, she swears to never eat or drink again to keep her lover’s taste in her mouth. She avoids the lord’s anger and his sword by leaping from a window to her death. Continue reading

e concerts under the title of Bach Through Time, the first of which featured Christophe Coin playing solo cello – or, in this case, two solo cellos with three different bows. He opened with one of the very first compositions for solo cello, the third of Domenico Gabrielli’s Ricercars, a lively piece in the trumpet key of D major which included many triad fanfare motifs. This Gabrielli (no relation) was part of the rich musical foundation of the Basilica of San Petronio in Bologna and also worked for the d’Este family in Moderna.

e concerts under the title of Bach Through Time, the first of which featured Christophe Coin playing solo cello – or, in this case, two solo cellos with three different bows. He opened with one of the very first compositions for solo cello, the third of Domenico Gabrielli’s Ricercars, a lively piece in the trumpet key of D major which included many triad fanfare motifs. This Gabrielli (no relation) was part of the rich musical foundation of the Basilica of San Petronio in Bologna and also worked for the d’Este family in Moderna.  Joan (more usually spelt as Juan) Cabanilles (1644–1712) is a curious composer. His compositions fully absorb the late Renaissance counterpoint of the earlier, and better known, Spanish organ composer Francisco Correa de Araujo (1584–1654) but apply to that foundation layers of often virtuosic Baroque figuration that can range in style from the simplistic to the frankly perverse. He was born in Valencia, and seems to have remained there throughout his life, engaged in little more than the usual activities of a priestly musician in a cathedral city. He was organist of the cathedral, but doesn’t seem to have ever become the cathedral’s musical director. Although he composed a vast amount of organ music, it was not published in his lifetime and none of his original manuscripts survive. His music only exists in copies, of varying degress of accuracy, most now housed in the Biblioteca de Catalunya in Barcelona. The Biblioteca began a problematical complete edition in 1927, which remains incomplete to this day.

Joan (more usually spelt as Juan) Cabanilles (1644–1712) is a curious composer. His compositions fully absorb the late Renaissance counterpoint of the earlier, and better known, Spanish organ composer Francisco Correa de Araujo (1584–1654) but apply to that foundation layers of often virtuosic Baroque figuration that can range in style from the simplistic to the frankly perverse. He was born in Valencia, and seems to have remained there throughout his life, engaged in little more than the usual activities of a priestly musician in a cathedral city. He was organist of the cathedral, but doesn’t seem to have ever become the cathedral’s musical director. Although he composed a vast amount of organ music, it was not published in his lifetime and none of his original manuscripts survive. His music only exists in copies, of varying degress of accuracy, most now housed in the Biblioteca de Catalunya in Barcelona. The Biblioteca began a problematical complete edition in 1927, which remains incomplete to this day.  The completion of the restoration of the famous 1735 Richard Bridge organ in Hawksmoor’s Christ Church, Spitalfields was one of the most important musical events in London during 2015. My review of John Scott’s opening recital, and details of the organ, can be seen

The completion of the restoration of the famous 1735 Richard Bridge organ in Hawksmoor’s Christ Church, Spitalfields was one of the most important musical events in London during 2015. My review of John Scott’s opening recital, and details of the organ, can be seen  designed by the famed Baroque architect Nicholas Hawksmoor. The organ was built in 1735 by Richard Bridge, who became one of the leading organ builders of the day. Spitalfields seems to have been only his second commission, perhaps explaining the comparatively low price of £600 for such a substantial instrument. For the following 100 years or so, it was the largest organ in the country. It suffered the inevitable changes over the years, but retained enough of its original pipework to form the basis for a historically based reconstruction, returning it broadly to its original specification and construction. It was dismantled in 1998 while the church was being restored and was then restored to its 1735 specification, with very few concessions. Its completion in 2015 makes this by far the most important pre-1800 organ in the UK.

designed by the famed Baroque architect Nicholas Hawksmoor. The organ was built in 1735 by Richard Bridge, who became one of the leading organ builders of the day. Spitalfields seems to have been only his second commission, perhaps explaining the comparatively low price of £600 for such a substantial instrument. For the following 100 years or so, it was the largest organ in the country. It suffered the inevitable changes over the years, but retained enough of its original pipework to form the basis for a historically based reconstruction, returning it broadly to its original specification and construction. It was dismantled in 1998 while the church was being restored and was then restored to its 1735 specification, with very few concessions. Its completion in 2015 makes this by far the most important pre-1800 organ in the UK. With an appropriate sense of timing, this CD was released on the day that it was announced that the distinguished countertenor Iestyn Davies was awarded an MBE in the Queen’s New Year’s honours list. For non-UK readers, this is the archaically entitled ‘Member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire’ and is awarded for ‘outstanding achievement’. There are at least four higher categories of ‘British Empire’ awards for him to look forward to. This is the third recording he has made with Arcangelo for Hyperion, but this one is very clearly a recording designed specifically to promote Iestyn Davies. His name is given stronger emphasis on the CD cover than the likes of Bach, let alone Arcangelo and Jonathan Cohen, all also pretty good musicians.

With an appropriate sense of timing, this CD was released on the day that it was announced that the distinguished countertenor Iestyn Davies was awarded an MBE in the Queen’s New Year’s honours list. For non-UK readers, this is the archaically entitled ‘Member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire’ and is awarded for ‘outstanding achievement’. There are at least four higher categories of ‘British Empire’ awards for him to look forward to. This is the third recording he has made with Arcangelo for Hyperion, but this one is very clearly a recording designed specifically to promote Iestyn Davies. His name is given stronger emphasis on the CD cover than the likes of Bach, let alone Arcangelo and Jonathan Cohen, all also pretty good musicians.  What a great CD, with the bonus of an fascinating back-story! It reflects the music of the exiled court in Rome of Henry Benedict Stuart (1725–1807) during the latter half of the 18th century. Henry Stuart is one of the most interesting characters in the complex world of 18th British politics, religion and royal succession. He was the grandson of deposed King James II of England (and VII of Scotland), son of the ‘Old Pretender’, brother of the ‘Young Pretender’ Bonnie Prince Charlie, and the last in the acknowledged direct line of Jacobite succession to the crown of Great Britain.By the time he was born, in Rome, the Crown had already passed to the German Hanoverians, despite there being more than 50 far better claimants to the throne in terms of blood relations to Queen Anne. But the British Parliament had passed a law preventing a Catholic from inheriting the throne. Unlike his father and brother, Henry Stuart made no active claim to the throne, although he was referred to by his own followers as King Henry IX of England and Ireland (and I of Scotland). Just after his birth he was created Duke of York in the Jacobite Peerage, and recognised as such in Catholic Europe but not in Great Britain.

What a great CD, with the bonus of an fascinating back-story! It reflects the music of the exiled court in Rome of Henry Benedict Stuart (1725–1807) during the latter half of the 18th century. Henry Stuart is one of the most interesting characters in the complex world of 18th British politics, religion and royal succession. He was the grandson of deposed King James II of England (and VII of Scotland), son of the ‘Old Pretender’, brother of the ‘Young Pretender’ Bonnie Prince Charlie, and the last in the acknowledged direct line of Jacobite succession to the crown of Great Britain.By the time he was born, in Rome, the Crown had already passed to the German Hanoverians, despite there being more than 50 far better claimants to the throne in terms of blood relations to Queen Anne. But the British Parliament had passed a law preventing a Catholic from inheriting the throne. Unlike his father and brother, Henry Stuart made no active claim to the throne, although he was referred to by his own followers as King Henry IX of England and Ireland (and I of Scotland). Just after his birth he was created Duke of York in the Jacobite Peerage, and recognised as such in Catholic Europe but not in Great Britain.

Over the years, William Christie has done much to introduce French baroque music to British ears, and has opened our ears to Purcell. But I had not heard his take on Messiah live before. It was bound to be rather different from the usual variety of British interpretations, and it was. We are increasingly used to lightly scored performances with moderately sized choirs, in contrast to the cast of thousands of yesteryear, but this very Gallic interpretation added a layer of delicacy and dance-like joie de vivre to Handel’s music, all done in the best possible Bon Goût. Les Arts Florissants fielded a choir of 24 (quite large, by some standards today, and in Handel’s time) and an orchestra with 6, 6, 4, 4, 2 strings, together with five soloists. Both instrumentalists and the chorus were encouraged to keep the volume down, usually by a finger on the Christie lips. This seems to be in line with Handel’s intentions, as indicated by his scoring and, for example, his very limited use of the trumpets. When things did let rip, there was still a sense of restraint amongst the power.

Over the years, William Christie has done much to introduce French baroque music to British ears, and has opened our ears to Purcell. But I had not heard his take on Messiah live before. It was bound to be rather different from the usual variety of British interpretations, and it was. We are increasingly used to lightly scored performances with moderately sized choirs, in contrast to the cast of thousands of yesteryear, but this very Gallic interpretation added a layer of delicacy and dance-like joie de vivre to Handel’s music, all done in the best possible Bon Goût. Les Arts Florissants fielded a choir of 24 (quite large, by some standards today, and in Handel’s time) and an orchestra with 6, 6, 4, 4, 2 strings, together with five soloists. Both instrumentalists and the chorus were encouraged to keep the volume down, usually by a finger on the Christie lips. This seems to be in line with Handel’s intentions, as indicated by his scoring and, for example, his very limited use of the trumpets. When things did let rip, there was still a sense of restraint amongst the power.  The Renaissance Singers have a history that goes back to 1944. They played an important part in the revival of interest in Renaissance sacred polyphony as the early music movement grew and developed. Their 2017 Christmas concert, in the architecturally important Hawksmoor church of St George’s Bloomsbury, sensibly avoided carols and concentrated on what they do best: singing Renaissance music. Under the inspired direction of their musical director, David Allinson, they presented a programme of seasonal music centered on the composer Clemens non Papa and his Missa Pastores quidnam vidistis, together with music by Josquin, Verdelot, Gombert and Willaert.

The Renaissance Singers have a history that goes back to 1944. They played an important part in the revival of interest in Renaissance sacred polyphony as the early music movement grew and developed. Their 2017 Christmas concert, in the architecturally important Hawksmoor church of St George’s Bloomsbury, sensibly avoided carols and concentrated on what they do best: singing Renaissance music. Under the inspired direction of their musical director, David Allinson, they presented a programme of seasonal music centered on the composer Clemens non Papa and his Missa Pastores quidnam vidistis, together with music by Josquin, Verdelot, Gombert and Willaert. The 31st St John’s, Smith Square Christmas Festival features most of the usual suspects, including regulars, The Cardinall’s Musick. As is typical of their concerts, the focus was on Catholic liturgical music from the Renaissance, on this occasion in honour of the Virgin Mary. In a ‘greatest hits’ line-up of Renaissance composers, the first half was built around Lassus’s Missa Osculeter me osculo oris sui alternating with motets by Victoria; the second centered on Byrd’s Propers for the Nativity of the Virgin Mary and concluded with Palestrina’s Magnificat primi toni a 8.

The 31st St John’s, Smith Square Christmas Festival features most of the usual suspects, including regulars, The Cardinall’s Musick. As is typical of their concerts, the focus was on Catholic liturgical music from the Renaissance, on this occasion in honour of the Virgin Mary. In a ‘greatest hits’ line-up of Renaissance composers, the first half was built around Lassus’s Missa Osculeter me osculo oris sui alternating with motets by Victoria; the second centered on Byrd’s Propers for the Nativity of the Virgin Mary and concluded with Palestrina’s Magnificat primi toni a 8.  The Wells choir dates back to the year 909 with the earliest mention of singing boys, the full choral tradition going back around 800 years.For more than 1000 years, the tradition of cathedral choirs is one of the foundations of the UK music industry, nurturing an enormous number of young musicians (albeit almost exclusively the male offspring of white middle-class parents) and then providing employment for some of them in later life. After a 1991 equal opportunities challenge in the European Court, Salisbury became the first cathedral to start a girls choir and the male domination has been lowly decreasing. Wells started their girls choir 3 years later, although curiously they do not usually sing together with the companion boys choir. However this CD uses both It is billed as “an irresistible array of popular carols and more recent offerings” and a “scintillating and varied programme vividly realised by the combined boy and girl choristers and Vicars Choral”.

The Wells choir dates back to the year 909 with the earliest mention of singing boys, the full choral tradition going back around 800 years.For more than 1000 years, the tradition of cathedral choirs is one of the foundations of the UK music industry, nurturing an enormous number of young musicians (albeit almost exclusively the male offspring of white middle-class parents) and then providing employment for some of them in later life. After a 1991 equal opportunities challenge in the European Court, Salisbury became the first cathedral to start a girls choir and the male domination has been lowly decreasing. Wells started their girls choir 3 years later, although curiously they do not usually sing together with the companion boys choir. However this CD uses both It is billed as “an irresistible array of popular carols and more recent offerings” and a “scintillating and varied programme vividly realised by the combined boy and girl choristers and Vicars Choral”. The Sixteen’s Christmas offering combines traditional with contemporary-lite pieces that, according to the Coro website “by their unashamed simplicity, captures the joy and sincerity of this most wonderful of seasons. This album provides a perfect peaceful and uplifting antidote to the hectic pre-Christmas rush.”. That sums it up pretty well. The composers represented range from Henry Walford Davies (b.1869) to still-living composers ranging from Morten Lauridsen (b.1943) to the youngest composer, Will Todd (b.1970). With what I assume is aimed at a Classic FM audience that The Sixteen seem to have captivated, there is nothing to frighten the musical horses but, equally little, if anything, to encourage younger or more adventurous composers.

The Sixteen’s Christmas offering combines traditional with contemporary-lite pieces that, according to the Coro website “by their unashamed simplicity, captures the joy and sincerity of this most wonderful of seasons. This album provides a perfect peaceful and uplifting antidote to the hectic pre-Christmas rush.”. That sums it up pretty well. The composers represented range from Henry Walford Davies (b.1869) to still-living composers ranging from Morten Lauridsen (b.1943) to the youngest composer, Will Todd (b.1970). With what I assume is aimed at a Classic FM audience that The Sixteen seem to have captivated, there is nothing to frighten the musical horses but, equally little, if anything, to encourage younger or more adventurous composers.

Since 2013, Seconda Pratica has been involved with the

Since 2013, Seconda Pratica has been involved with the  The

The  For many years now, Spitalfields Music has been spreading its wings way beyond its original home in Spitalfields, both for its major programme of community work and for venues for its musical and other performances. It is now a major arts and community organisation covering the whole of the East End of London. Among the venues for this year’s winter festival (which included a hidden Masonic Temple) was The Octagon, built in 1887 as part of the grand premises of the People’s Palace, described in The Times on its opening as a “happy experiment in practical Socialism”. It is now the home of Queen Mary University of London. The architect, ER Robson (best known for his influential school designs), used the British Museum Reading Room for inspiration in designing the octagonal library.

For many years now, Spitalfields Music has been spreading its wings way beyond its original home in Spitalfields, both for its major programme of community work and for venues for its musical and other performances. It is now a major arts and community organisation covering the whole of the East End of London. Among the venues for this year’s winter festival (which included a hidden Masonic Temple) was The Octagon, built in 1887 as part of the grand premises of the People’s Palace, described in The Times on its opening as a “happy experiment in practical Socialism”. It is now the home of Queen Mary University of London. The architect, ER Robson (best known for his influential school designs), used the British Museum Reading Room for inspiration in designing the octagonal library. More ‘happy experiments’ were in evidence in the programme ‘Sound House’ given by The Society of Strange and Ancient Instruments (SSAI). It was based on the 17th century scientific writings and acoustic experiments of Francis Bacon, as described in his posthumously published Sylva Sylcarum and New Atlantis. In the latter vision of a new society, Bacon promoted the idea of Sound Houses where his acoustic experiments could be continued and better appreciated by the populace. Bacon’s musical ideas might seem commonplace today, not least through the medium of electronics and manipulated sound, and his experimental approach to sound is a key feature of many musicians today.

More ‘happy experiments’ were in evidence in the programme ‘Sound House’ given by The Society of Strange and Ancient Instruments (SSAI). It was based on the 17th century scientific writings and acoustic experiments of Francis Bacon, as described in his posthumously published Sylva Sylcarum and New Atlantis. In the latter vision of a new society, Bacon promoted the idea of Sound Houses where his acoustic experiments could be continued and better appreciated by the populace. Bacon’s musical ideas might seem commonplace today, not least through the medium of electronics and manipulated sound, and his experimental approach to sound is a key feature of many musicians today. The Spitalfields Music Winter Festival is one of the highlights of the London musical calendar, sensibly positioned in early December just before the Christmas musical silliness takes hold. Founded in 1976, initially to raise interest and money for the restoration of the fabulous Nicholas Hawksmoor Christ Church Spitalfields, Spitalfields Music has grown to became a major arts and community organisation working throughout the year in the East End of London. It’s 40th year included 15 new commissions, programming more than 65 performances across East London, enabling some 5000 local people to take part in free musical activities, and working with communities ranging from 1500 local school children to care home residents. The week-long festival ranged from contemporary jazz, a Bollywood show with ‘a tuba the size of Belgium’, a show for toddlers, musical dinners in a hidden Masonic Temple together with the usual array of top-notch classical music events, with the usual focus on early and contemporary music.

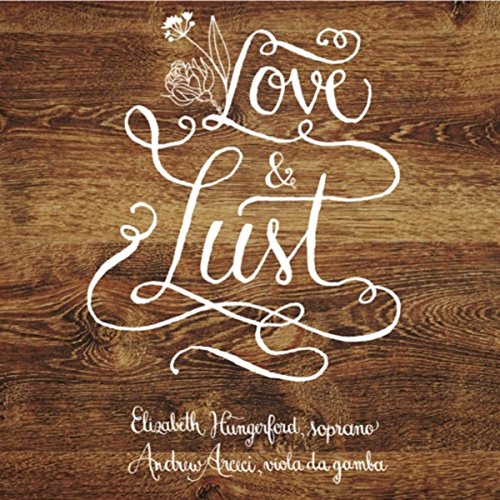

The Spitalfields Music Winter Festival is one of the highlights of the London musical calendar, sensibly positioned in early December just before the Christmas musical silliness takes hold. Founded in 1976, initially to raise interest and money for the restoration of the fabulous Nicholas Hawksmoor Christ Church Spitalfields, Spitalfields Music has grown to became a major arts and community organisation working throughout the year in the East End of London. It’s 40th year included 15 new commissions, programming more than 65 performances across East London, enabling some 5000 local people to take part in free musical activities, and working with communities ranging from 1500 local school children to care home residents. The week-long festival ranged from contemporary jazz, a Bollywood show with ‘a tuba the size of Belgium’, a show for toddlers, musical dinners in a hidden Masonic Temple together with the usual array of top-notch classical music events, with the usual focus on early and contemporary music. This CD was recorded in 2013 and appears to have been available as a download, but was issued as a CD in 2014 or 15. It appears to be self-produced, as there is no record label mentioned, although the bar code number listed above is searchable. The CD liner notes give translations of the texts, but not strictly in the order of the tracks. No track or total timings are given, which might limit its use for broadcasters. There is a brief note about the two performers, but no other information about the programme or the background to the pieces. But there is a full page listing of some 150 people who “the artists wish to thank” – presumably the result of a crowdfunding campaign.

This CD was recorded in 2013 and appears to have been available as a download, but was issued as a CD in 2014 or 15. It appears to be self-produced, as there is no record label mentioned, although the bar code number listed above is searchable. The CD liner notes give translations of the texts, but not strictly in the order of the tracks. No track or total timings are given, which might limit its use for broadcasters. There is a brief note about the two performers, but no other information about the programme or the background to the pieces. But there is a full page listing of some 150 people who “the artists wish to thank” – presumably the result of a crowdfunding campaign. Unless you have been weaned on the sound of brass bands (which I wasn’t) the sounds and the instruments on this recording might appear rather unusual. It features no fewer than seven saxhorns, ranging from contralto to contrabass, along with five different cornets, and a ventil horn, all dating from around 1850-1900 (pictured below). The five players of the period brass ensemble, The Prince Regent’s Band, share these out amongst themselves as they explore the music of the extraordinary Distin family who, between 1835 and 1857, journeyed around Europe and North America performing and promoting new designs of brass instruments. They were instrumental, so to speak, in the development of new valved instruments, one being the saxhorn, designed by Adolphe Sax (who they met in Paris in 1844) but improved by the Distins, who gave the instrument its name.

Unless you have been weaned on the sound of brass bands (which I wasn’t) the sounds and the instruments on this recording might appear rather unusual. It features no fewer than seven saxhorns, ranging from contralto to contrabass, along with five different cornets, and a ventil horn, all dating from around 1850-1900 (pictured below). The five players of the period brass ensemble, The Prince Regent’s Band, share these out amongst themselves as they explore the music of the extraordinary Distin family who, between 1835 and 1857, journeyed around Europe and North America performing and promoting new designs of brass instruments. They were instrumental, so to speak, in the development of new valved instruments, one being the saxhorn, designed by Adolphe Sax (who they met in Paris in 1844) but improved by the Distins, who gave the instrument its name.

Composers with an eye for future recognition should ideally aim to die around the age of either 25 or 75, thereby gaining an anniversary every 25 years or so. Johann Jakob Froberger (1616-67) died aged 51, which means that he has anniversaries this year and next year, but not again for another 49 years. Hopefully the burst of interest in these two years will carry his name forward, as he is an often overlooked composer. But he was an enormous influence on keyboard composers from the 17th to early 19th century, not least for spreading the Italian style of his teacher Frescobaldi around Europe, and assimilating various European musical styles into his own compositions, notably from France.

Composers with an eye for future recognition should ideally aim to die around the age of either 25 or 75, thereby gaining an anniversary every 25 years or so. Johann Jakob Froberger (1616-67) died aged 51, which means that he has anniversaries this year and next year, but not again for another 49 years. Hopefully the burst of interest in these two years will carry his name forward, as he is an often overlooked composer. But he was an enormous influence on keyboard composers from the 17th to early 19th century, not least for spreading the Italian style of his teacher Frescobaldi around Europe, and assimilating various European musical styles into his own compositions, notably from France. What a fascinating recording!

What a fascinating recording!