Andrew Benson-Wilson plays music by

Matthias Weckmann (1616-1674)

on the famous Frobenius organ in the Chapel of The Queen’s College, Oxford.

27 April 2016, 13:10.

A recital of organ music by the Hamburg master organist/composer, Matthias Weckmann, born 400 years ago this year. A pupil of Schütz who, in turn, was a pupil of Giovanni Gabrieli, Weckmann studied and worked in Dresden and Denmark. A friend of the influential Froberger, Weckmann settled in Hamburg in 1655 as organist of the Jakobikirche. He died in 1674 and is buried beneath the Jakobikirche organ.

Praeambulum Primi toni a 5

Ach wir armen Sünder (3v)

Canzon V

Magnificat Secundi Toni (4v)

Toccata ex D

Gelobet seystu, Jesu Christ (4v)

Programme note here.

Admission free – retiring collection. Organ information here.

See also www.organrecitals.com/abw.

The medieval cult of saintly relics has left us with some glorious examples of art, architecture, literature and music. But the studies of historians generally focus on one of first three of these aspects in isolation. This book aims to redress the balance by focussing on the musical aspects but within the context of the rich story of politics, power and influence, the complex history of monasticism and liturgy, and the artistic outpouring that the devotion to relics generated. It covers the period from around the mid-eighth century to the thirteenth in Tuscany. It is an extension of a Yale PhD thesis by musicologist Benjamin Brand.

The medieval cult of saintly relics has left us with some glorious examples of art, architecture, literature and music. But the studies of historians generally focus on one of first three of these aspects in isolation. This book aims to redress the balance by focussing on the musical aspects but within the context of the rich story of politics, power and influence, the complex history of monasticism and liturgy, and the artistic outpouring that the devotion to relics generated. It covers the period from around the mid-eighth century to the thirteenth in Tuscany. It is an extension of a Yale PhD thesis by musicologist Benjamin Brand. The UK seems to breed small-scale a capella male choral groups. The aptly named Queen’s Six are one of a particular branch of that breed, with their matching suits and shirts (and, it seems, overcoats) and carefully posed publicity photographs. They are half of the contingent of lay clerks (adult choir singers) at St George’s Chapel in Windsor Castle, an official residence of the Queen as well as her private weekend home. Living within the castle walls, and performing eight or more services a week in the Royal Chapel; the six male singer’s vocal credentials couldn’t be greater. They were formed in 2008 on the 450th anniversary of Queen Elizabeth I,

The UK seems to breed small-scale a capella male choral groups. The aptly named Queen’s Six are one of a particular branch of that breed, with their matching suits and shirts (and, it seems, overcoats) and carefully posed publicity photographs. They are half of the contingent of lay clerks (adult choir singers) at St George’s Chapel in Windsor Castle, an official residence of the Queen as well as her private weekend home. Living within the castle walls, and performing eight or more services a week in the Royal Chapel; the six male singer’s vocal credentials couldn’t be greater. They were formed in 2008 on the 450th anniversary of Queen Elizabeth I,  A number of churches are accepting the inevitable reduction in congregations and opening their buildings to wider community use. Heath Street Baptist Church, prominently positioned in the middle of Hampstead, is one such, reducing their services to Sunday mornings, but enabling a wide variety of activities during the rest of the week, including frequent lunchtime and evening concerts and, on this occasion, a complete weekend devoted to the ‘Hampstead Baroque Festival’. After four earlier events of English, Italian and French music, all accompanied by food, the weekend concluded with a Sunday evening concert devoted to ‘Bratwurst, Beer & Bach’, given by the newly-formed group L’Istante (not, incidentally, the only early music group to adopt that name *and now renamed as Isante) directed by harpsichordist/conductor Pawel Siwzak.

A number of churches are accepting the inevitable reduction in congregations and opening their buildings to wider community use. Heath Street Baptist Church, prominently positioned in the middle of Hampstead, is one such, reducing their services to Sunday mornings, but enabling a wide variety of activities during the rest of the week, including frequent lunchtime and evening concerts and, on this occasion, a complete weekend devoted to the ‘Hampstead Baroque Festival’. After four earlier events of English, Italian and French music, all accompanied by food, the weekend concluded with a Sunday evening concert devoted to ‘Bratwurst, Beer & Bach’, given by the newly-formed group L’Istante (not, incidentally, the only early music group to adopt that name *and now renamed as Isante) directed by harpsichordist/conductor Pawel Siwzak. Overtures by: Nicolai, Spohr, Bach, Handel, Verdi, Weber, Tchaikovsky;

Overtures by: Nicolai, Spohr, Bach, Handel, Verdi, Weber, Tchaikovsky; Although the sub-title, ‘Favourite anthems from Merton’, might not be quite accurate for every potential listener, this collection of anthems certainly represents a fascinating insight into Oxbridge choral tradition and its music. It opens with the premiere recording of Jonathan Dove’s Te Deum, a paean of praise with an exciting accompaniment that shows off their new organ. In a very mixed programme, we then have Tallis’s exquisite little If ye love me, before Elgar arrives with Give unto the Lord before giving way to Thomas Morley, a rather dramatic switch of musical styles. And so it continues, with Rutter, Parry, Quilter, Finzi, Harris and Patrick Gowers interweaved between Byrd and more Tallis.

Although the sub-title, ‘Favourite anthems from Merton’, might not be quite accurate for every potential listener, this collection of anthems certainly represents a fascinating insight into Oxbridge choral tradition and its music. It opens with the premiere recording of Jonathan Dove’s Te Deum, a paean of praise with an exciting accompaniment that shows off their new organ. In a very mixed programme, we then have Tallis’s exquisite little If ye love me, before Elgar arrives with Give unto the Lord before giving way to Thomas Morley, a rather dramatic switch of musical styles. And so it continues, with Rutter, Parry, Quilter, Finzi, Harris and Patrick Gowers interweaved between Byrd and more Tallis. When I first saw the cover of this CD and the names of the performers, I started looking to see if this was a re-release of an earlier recording. But it is a new recording, made in 2015, featuring the distinguished names of singers Emily Van Evera and Charles Daniels, alongside Andrew Parrott and his Taverner Choir and Players. Most recordings or concerts based on a Mass setting interweave vocal motets around the usual Mass movements in an attempted liturgical reconstruction but, very refreshingly, this CD incorporates a miscellany of instrumental and vocal music related to the Court of Henry VIII alongside The Western Wynde Mass by John Taverner, an almost exact contemporary of the King.

When I first saw the cover of this CD and the names of the performers, I started looking to see if this was a re-release of an earlier recording. But it is a new recording, made in 2015, featuring the distinguished names of singers Emily Van Evera and Charles Daniels, alongside Andrew Parrott and his Taverner Choir and Players. Most recordings or concerts based on a Mass setting interweave vocal motets around the usual Mass movements in an attempted liturgical reconstruction but, very refreshingly, this CD incorporates a miscellany of instrumental and vocal music related to the Court of Henry VIII alongside The Western Wynde Mass by John Taverner, an almost exact contemporary of the King. The players of the Early Opera Company, directed by Christian Curnyn, stepped out of their more usual orchestra pit for an almost instrumental evening of music making at St John’s, Smith Square, with music generally representing the Concerto Grosso format.

The players of the Early Opera Company, directed by Christian Curnyn, stepped out of their more usual orchestra pit for an almost instrumental evening of music making at St John’s, Smith Square, with music generally representing the Concerto Grosso format. The Brook Street Band, named after the London street where Handel lived for the last 36 years of his life, celebrate their 20th anniversary this year. As well as his well known Opus 2 and 5 sets of Trio Sonatas, Handel left a number of isolated examples of the genre, three of them normally referred to as the ‘Dresden’ sonatas where the manuscript is housed. To these three (HWV 392-4), are added two other proper trio sonatas (386a and 403) and two other pieces arranged by the Brook Street Band in a trio sonata format, the early Sinfonia and an early version of the overture to Esther, both of which helpfully lack an viola part. Many of the movements are examples of Handel’s re-use of material, and there are a number of familiar melodies that crop up with an otherwise lesser known group of pieces. Notable amongst

The Brook Street Band, named after the London street where Handel lived for the last 36 years of his life, celebrate their 20th anniversary this year. As well as his well known Opus 2 and 5 sets of Trio Sonatas, Handel left a number of isolated examples of the genre, three of them normally referred to as the ‘Dresden’ sonatas where the manuscript is housed. To these three (HWV 392-4), are added two other proper trio sonatas (386a and 403) and two other pieces arranged by the Brook Street Band in a trio sonata format, the early Sinfonia and an early version of the overture to Esther, both of which helpfully lack an viola part. Many of the movements are examples of Handel’s re-use of material, and there are a number of familiar melodies that crop up with an otherwise lesser known group of pieces. Notable amongst  Magnificat vocal ensemble celebrate their 25th anniversary with this CD of extraordinarily powerful large-scale polyphonic works by Renaissance masters, all influenced by the equally extraordinary Italian Dominican friar and prophet, Girolamo Savonarola. His rather alarming prophesies (including declaring Florence to be the ‘New Jerusalem’, the destruction of all things secular, and a biblical flood), his denouncement of the Medicis, clerical corruption, and the exploitation of the poor, together with his extreme puritanical views (resulting in the Bonfire of the Vanities) led, not surprisingly, to his getting himself caught up in Italian and Papal politics.

Magnificat vocal ensemble celebrate their 25th anniversary with this CD of extraordinarily powerful large-scale polyphonic works by Renaissance masters, all influenced by the equally extraordinary Italian Dominican friar and prophet, Girolamo Savonarola. His rather alarming prophesies (including declaring Florence to be the ‘New Jerusalem’, the destruction of all things secular, and a biblical flood), his denouncement of the Medicis, clerical corruption, and the exploitation of the poor, together with his extreme puritanical views (resulting in the Bonfire of the Vanities) led, not surprisingly, to his getting himself caught up in Italian and Papal politics. The programme notes explain the rational for recording these pieces on clavichord rather than harpsichord, with a convincing argument based on the four-octave compass of the pieces and the didactic nature of their composition, in this case, for his recent (and second) wife Anna Magdalena. This is private, domestic music for home performance or teaching purposes, rather than the more elaborate pieces Bach wrote for public performance, using the larger compass of the harpsichord, for example the three non-organ parts of the Clavierübung. It is also the case that the clavichord was the principal home practice instrument for organists, because the arm to finger weight transfer required is similar for both instruments.

The programme notes explain the rational for recording these pieces on clavichord rather than harpsichord, with a convincing argument based on the four-octave compass of the pieces and the didactic nature of their composition, in this case, for his recent (and second) wife Anna Magdalena. This is private, domestic music for home performance or teaching purposes, rather than the more elaborate pieces Bach wrote for public performance, using the larger compass of the harpsichord, for example the three non-organ parts of the Clavierübung. It is also the case that the clavichord was the principal home practice instrument for organists, because the arm to finger weight transfer required is similar for both instruments. This is a re-release and re-packaging of a recording made in 2003 (first released in 2008) which stemmed from musicologist Francesco Zimei, the Institute of Musical History of Abruzzo, and a conference in Teramo that aimed to revive the music of the fascinating character, Antonio Zacara da Teramo. Antonio was active around 1400. The rather unkind nickname Zacara (which could mean a small thing, a thing of little value, or a splash of mud) stems from his being rather short in stature, and having a range of physical deformities (possible a result of what later became known as phocomelia) including several missing fingers, as depicted in the Codex Squarcialupi illustration.

This is a re-release and re-packaging of a recording made in 2003 (first released in 2008) which stemmed from musicologist Francesco Zimei, the Institute of Musical History of Abruzzo, and a conference in Teramo that aimed to revive the music of the fascinating character, Antonio Zacara da Teramo. Antonio was active around 1400. The rather unkind nickname Zacara (which could mean a small thing, a thing of little value, or a splash of mud) stems from his being rather short in stature, and having a range of physical deformities (possible a result of what later became known as phocomelia) including several missing fingers, as depicted in the Codex Squarcialupi illustration.  Christ’s Chapel of Alleyn’s College of God’s Gift in Dulwich was consecrated 400 years ago, in 1616. The chapel and adjoining almshouses were the first of the charity foundations set up by the wealthy actor, Edward Alleyn, owner of the manor of Dulwich. Shortly afterwards, the foundation’s status as a educational college was confirmed, leading to the present day Dulwich College.

Christ’s Chapel of Alleyn’s College of God’s Gift in Dulwich was consecrated 400 years ago, in 1616. The chapel and adjoining almshouses were the first of the charity foundations set up by the wealthy actor, Edward Alleyn, owner of the manor of Dulwich. Shortly afterwards, the foundation’s status as a educational college was confirmed, leading to the present day Dulwich College. time the Chapel’s first organ was installed. In 1760 it was replaced by a new organ by George England which, despite the usual additions and alterations over the years, still survives with a considerable amount of mid- 18th century pipework and a fine Gothick case. In 2009 it was restored back to its 1760 state (with modest additions) by the UK’s leading specialist on historic organs, William Drake. The original pitch (A430) and modified fifth-comma meantone temperament was restored. It is now one of the most important historic instruments in the UK.

time the Chapel’s first organ was installed. In 1760 it was replaced by a new organ by George England which, despite the usual additions and alterations over the years, still survives with a considerable amount of mid- 18th century pipework and a fine Gothick case. In 2009 it was restored back to its 1760 state (with modest additions) by the UK’s leading specialist on historic organs, William Drake. The original pitch (A430) and modified fifth-comma meantone temperament was restored. It is now one of the most important historic instruments in the UK. opening with Bach bustling Sinfonia from the cantata Am Adend aber desselbigen Sabbats, composed in 1725, the lengthy instrumental opening (pictured) was apparently intended to give the singers a bit of a break after a busy week. It has a jovial, extended and rather convoluted initial theme which bubbles along until a concluding, and very clever, skipped beat. A conversation between strings and two oboes and bassoon, this is the type of piece that Bach probably scribbled down before breakfast but, 300 years later, stands as an extraordinary example of his genius and skill at turning a string of notes into something inspired and divine.

opening with Bach bustling Sinfonia from the cantata Am Adend aber desselbigen Sabbats, composed in 1725, the lengthy instrumental opening (pictured) was apparently intended to give the singers a bit of a break after a busy week. It has a jovial, extended and rather convoluted initial theme which bubbles along until a concluding, and very clever, skipped beat. A conversation between strings and two oboes and bassoon, this is the type of piece that Bach probably scribbled down before breakfast but, 300 years later, stands as an extraordinary example of his genius and skill at turning a string of notes into something inspired and divine. Singer Clara Sanabras arrived in London from her Barcelona home about 20 years ago to study music, despite not speaking a word of English. I first reviewed her shortly after her arrival in one of the many early music groups that she went on to perform with, noting that she has “an evocatively sensual and focussed voice, rich with harmonics . . . her voice is ideal for much of the early repertoire, particularly from the medieval and early renaissance”. She has since built an enviable reputation as an eclectic singer/songwriter with a wide variety of musical styles, notably in the broadly folk/blues tradition. I wrote in a later review that “I hope that Sanabras is not lost to the early music world”. She hasn’t been, and has certainly not lost the clarity, purity and superb intonation of her evocative and sensuous voice. But there aren’t many early music solo singers who could fill The Barbican hall for a concert of her own compositions, complete with over 200 supporting musicians.

Singer Clara Sanabras arrived in London from her Barcelona home about 20 years ago to study music, despite not speaking a word of English. I first reviewed her shortly after her arrival in one of the many early music groups that she went on to perform with, noting that she has “an evocatively sensual and focussed voice, rich with harmonics . . . her voice is ideal for much of the early repertoire, particularly from the medieval and early renaissance”. She has since built an enviable reputation as an eclectic singer/songwriter with a wide variety of musical styles, notably in the broadly folk/blues tradition. I wrote in a later review that “I hope that Sanabras is not lost to the early music world”. She hasn’t been, and has certainly not lost the clarity, purity and superb intonation of her evocative and sensuous voice. But there aren’t many early music solo singers who could fill The Barbican hall for a concert of her own compositions, complete with over 200 supporting musicians. This is re-launch and revision of a 2003 recording of the 13th century Pastourelle, ‘The Game of Robin and Marion’, telling the story of an encounter between the knight Aubert, the shepherdess Marion, and her lover Robin and his attempts to rescue her from his advances. The staged drama was written in 1284 for the Naples Court of the French Charles of Anjou, King of Sicily, shortly after the Sicilian Vespers had ousted him from Sicily itself. It was possibly intended to reflect a longing for their French homeland, but with undertones of Crusading mythology and the massacre of the French forces at Palermo. It is an early example of the genre of musical theatre.

This is re-launch and revision of a 2003 recording of the 13th century Pastourelle, ‘The Game of Robin and Marion’, telling the story of an encounter between the knight Aubert, the shepherdess Marion, and her lover Robin and his attempts to rescue her from his advances. The staged drama was written in 1284 for the Naples Court of the French Charles of Anjou, King of Sicily, shortly after the Sicilian Vespers had ousted him from Sicily itself. It was possibly intended to reflect a longing for their French homeland, but with undertones of Crusading mythology and the massacre of the French forces at Palermo. It is an early example of the genre of musical theatre.  The Birmingham based choir, Ex Cathedra has long been at the forefront of British choral music, notably through their educational work and concerts and recordings of early music and Baroque music from Central and South America, a particular research interest for their inspirational director, Jeffry Skidmore. But they also venture into more recent repertoire, as evidenced by their latest CD of music by Alex Roth.

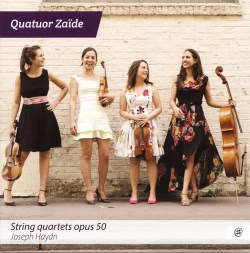

The Birmingham based choir, Ex Cathedra has long been at the forefront of British choral music, notably through their educational work and concerts and recordings of early music and Baroque music from Central and South America, a particular research interest for their inspirational director, Jeffry Skidmore. But they also venture into more recent repertoire, as evidenced by their latest CD of music by Alex Roth. Haydn’s Op.50 (Prussian) String Quartets are amongst his finest musical creations, and yet are relatively unknown, apart from the two given the later nicknames of The Dream and The Frog. Composed in 1787, the set was dedicated to Frederick William II of Prussia (apparently in return for a gold ring sent to Haydn by the King), hence the nickname. The fact that he played the cello might explain the opening of the first quartet, with its solo cello repetition of notes. The six quartets are perhaps less immediately appealing and populist than his earlier Op.33 set, and seem to feature Haydn in a more intense and, perhaps, more intellectual mood. The movements usually only explore one theme, perhaps suggesting that Haydn wanted to concentrate on the developmental possibilities of a single theme. Although each has the same four movement format, they are all very different in style, notably the 4th, in the dark key of F# minor, and with its curiously intensely wrought final fugue.

Haydn’s Op.50 (Prussian) String Quartets are amongst his finest musical creations, and yet are relatively unknown, apart from the two given the later nicknames of The Dream and The Frog. Composed in 1787, the set was dedicated to Frederick William II of Prussia (apparently in return for a gold ring sent to Haydn by the King), hence the nickname. The fact that he played the cello might explain the opening of the first quartet, with its solo cello repetition of notes. The six quartets are perhaps less immediately appealing and populist than his earlier Op.33 set, and seem to feature Haydn in a more intense and, perhaps, more intellectual mood. The movements usually only explore one theme, perhaps suggesting that Haydn wanted to concentrate on the developmental possibilities of a single theme. Although each has the same four movement format, they are all very different in style, notably the 4th, in the dark key of F# minor, and with its curiously intensely wrought final fugue.  This rather unusual CD reflects one of the glories of 19th century domestic music-making (itself reaching its zenith in that period), the repertoire for two voices and piano, in this case represented by Cornelius, Mendelssohn, and Schumann, three of the finest masters of the genre. Generally overlooked nowadays in favour of larger scale performances, this CD reflects a now almost completely forgotten aspect of earlier home life: music making centred on the domestic piano. However, in this case, the venue is more likely to be a saloon, given the recording acoustic of a church and the rather unauthentic use of a modern concert grand piano (given its own billing in the programme note as a Steinway model D, serial number 589064) rather than a period piano – or, indeed, the more likely upright to be found in most 19th century homes.

This rather unusual CD reflects one of the glories of 19th century domestic music-making (itself reaching its zenith in that period), the repertoire for two voices and piano, in this case represented by Cornelius, Mendelssohn, and Schumann, three of the finest masters of the genre. Generally overlooked nowadays in favour of larger scale performances, this CD reflects a now almost completely forgotten aspect of earlier home life: music making centred on the domestic piano. However, in this case, the venue is more likely to be a saloon, given the recording acoustic of a church and the rather unauthentic use of a modern concert grand piano (given its own billing in the programme note as a Steinway model D, serial number 589064) rather than a period piano – or, indeed, the more likely upright to be found in most 19th century homes.  This is a spectacular CD from the ever excellent Dunedin Consort and their leader, violinist Cecilia Bernardini, this time in a solo role. She opens and closes the programme in partnership, first with her father, the distinguished oboist, Alfredo Bernardini, and then with fellow violinist Huw Daniel. Apart from the short central Sinfonia from the cantata Ich hatte viel Bekümmernis, with its exquisite oboe solo, the rest of the nicely symmetrical programme is devoted to the playing of Cecilia Bernardini, with Bach’s E major and A minor violin concertos. And what playing it is. Subtly sensitive, and superbly articulated, she demonstrates a real grasp of Bach’s often complex melodic lines. Her delicacy of tone is matched by her fellow instrumentalists, the chamber-like quality of their playing, and John Butt’s direction and harpsichord continuo playing, being just right for the music, which was almost certainly intended for small-scale performance amongst fellow music lovers.

This is a spectacular CD from the ever excellent Dunedin Consort and their leader, violinist Cecilia Bernardini, this time in a solo role. She opens and closes the programme in partnership, first with her father, the distinguished oboist, Alfredo Bernardini, and then with fellow violinist Huw Daniel. Apart from the short central Sinfonia from the cantata Ich hatte viel Bekümmernis, with its exquisite oboe solo, the rest of the nicely symmetrical programme is devoted to the playing of Cecilia Bernardini, with Bach’s E major and A minor violin concertos. And what playing it is. Subtly sensitive, and superbly articulated, she demonstrates a real grasp of Bach’s often complex melodic lines. Her delicacy of tone is matched by her fellow instrumentalists, the chamber-like quality of their playing, and John Butt’s direction and harpsichord continuo playing, being just right for the music, which was almost certainly intended for small-scale performance amongst fellow music lovers.  It was a mark of the respect that the viola da gamba player, Richard Campbell, is held that so many people came to the Guildhall School of Music & Drama to celebrate his 60th birthday. The evening also marked the presentation to the Guildhall School of a Lirone and a Bandorra from Richard’s own collection, both to be made available to any young musician for study and performance. The choice of two such unusual instruments was a nice reflection of Richard’s wide-ranging musical interests.

It was a mark of the respect that the viola da gamba player, Richard Campbell, is held that so many people came to the Guildhall School of Music & Drama to celebrate his 60th birthday. The evening also marked the presentation to the Guildhall School of a Lirone and a Bandorra from Richard’s own collection, both to be made available to any young musician for study and performance. The choice of two such unusual instruments was a nice reflection of Richard’s wide-ranging musical interests.  Jacques le Polonois (aka Jakub Polak and Jakub/Jacob/Jacques Reys) was born around 1545 in Poland. He was court lutenist to Henry III (briefly the elected King of Poland before returning to France, with Polonois, where he had inherited the throne) and Henri IV of France. As a lute playing composer, his pieces tested the technical abilities of other players. Much later writers wrote (with uncertain evidence) of his ‘good and quick hand’, mentioning that he ‘got the very soul out of the lute’. His extemporisation skills were praised. He left around 60 works for the lute, nearly half of which are included on this recording, many first recordings. Many include the word Polonaise in the title, referring to his county of origin, rather than the national style of his music, which was firmly French. Versions of his names, Jacob and Reys, also appear in several titles.

Jacques le Polonois (aka Jakub Polak and Jakub/Jacob/Jacques Reys) was born around 1545 in Poland. He was court lutenist to Henry III (briefly the elected King of Poland before returning to France, with Polonois, where he had inherited the throne) and Henri IV of France. As a lute playing composer, his pieces tested the technical abilities of other players. Much later writers wrote (with uncertain evidence) of his ‘good and quick hand’, mentioning that he ‘got the very soul out of the lute’. His extemporisation skills were praised. He left around 60 works for the lute, nearly half of which are included on this recording, many first recordings. Many include the word Polonaise in the title, referring to his county of origin, rather than the national style of his music, which was firmly French. Versions of his names, Jacob and Reys, also appear in several titles. The link between early music performance and academic musicological study has always been close, but seems to be becoming even more so with a number of recent projects stemming directly from research backed by the Arts & Humanities Research Council (AHRC). One such is the project ‘Cantum pulcriorem invenire: Thirteenth-Century Music and Poetry’, based at Southampton University, headed by Mark Everist (details

The link between early music performance and academic musicological study has always been close, but seems to be becoming even more so with a number of recent projects stemming directly from research backed by the Arts & Humanities Research Council (AHRC). One such is the project ‘Cantum pulcriorem invenire: Thirteenth-Century Music and Poetry’, based at Southampton University, headed by Mark Everist (details  If you are mathematically minded, this might be the CD for you. Some of the most complex examples of English contrapuntal wizardry from Tallis and Byrd are balanced by more recent, but equally complex and evocative music, from the Estonian composer, Arvo Pärt. As the programme note explains, “Here, Tallis and Byrd meet Pärt on common ground”, although at times, Pärt’s music can sound earlier than that of Tallis and Byrd with its sense of mediaeval structure and texture. This CD will whet your appetite for The Sixteen’s 2016 Choral Pilgrimage, when you can experience this music performed live in some of the most beautiful venues the UK can offer.

If you are mathematically minded, this might be the CD for you. Some of the most complex examples of English contrapuntal wizardry from Tallis and Byrd are balanced by more recent, but equally complex and evocative music, from the Estonian composer, Arvo Pärt. As the programme note explains, “Here, Tallis and Byrd meet Pärt on common ground”, although at times, Pärt’s music can sound earlier than that of Tallis and Byrd with its sense of mediaeval structure and texture. This CD will whet your appetite for The Sixteen’s 2016 Choral Pilgrimage, when you can experience this music performed live in some of the most beautiful venues the UK can offer. (every other month) at St Michael’s, on South Grove, Highgate. They opened the series with a concert of music from the North German masters, Dietrich Buxtehude and his predecessor at the Lübeck Marienkirche (and father-in-law), Franz Tunder. Tunder is usually unfairly overlooked in favour of his successor, but it was he who started the famous series of Lübeck Abendmusik concerts that traditionally took place on the five Sundays before Christmas every year; a tradition that lasted until 1810. They (and the then aging Buxtehude) famously attracted the young Bach in 1705.

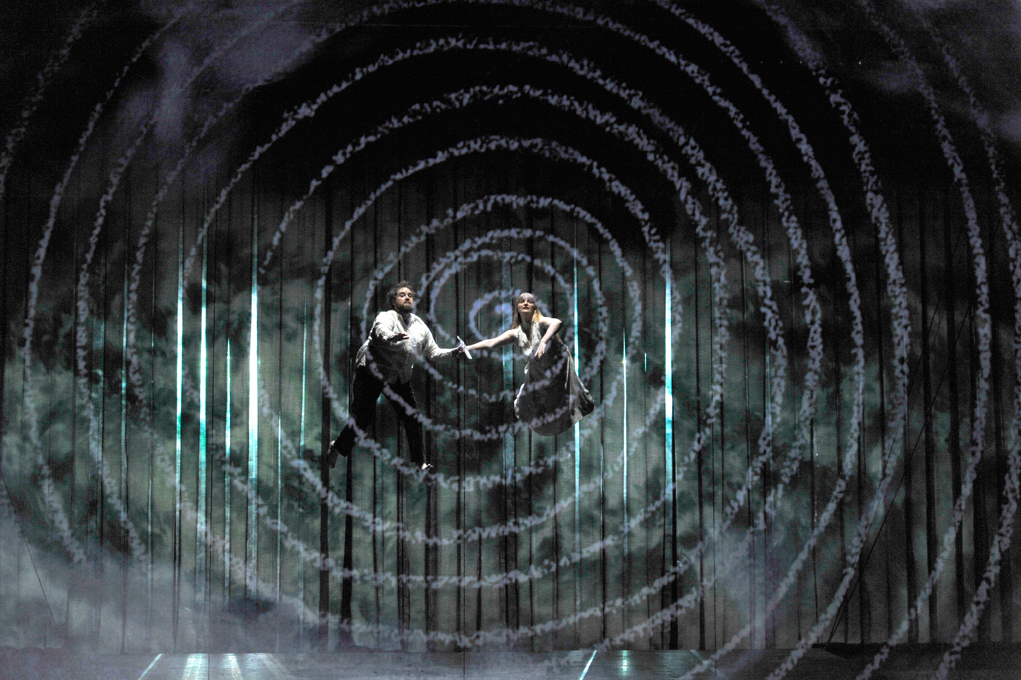

(every other month) at St Michael’s, on South Grove, Highgate. They opened the series with a concert of music from the North German masters, Dietrich Buxtehude and his predecessor at the Lübeck Marienkirche (and father-in-law), Franz Tunder. Tunder is usually unfairly overlooked in favour of his successor, but it was he who started the famous series of Lübeck Abendmusik concerts that traditionally took place on the five Sundays before Christmas every year; a tradition that lasted until 1810. They (and the then aging Buxtehude) famously attracted the young Bach in 1705.  nal take. My review of the opening of McBurney’s version included “In contrast to the previous production, this Magic Flute is dark, mysterious and more than a little weird. A flood of ideas drenched the stage, aided by a commentator sitting in a box in the corner, chalking up comments onto a large video screen. But there seems, at least to me, on first sight, little coherence to link it all together. Masonic references are played down, but the element of cult is still stressed through colour-coded camps in conflict . . . It may well be that, in 25 years time, I will miss this production. But, in the meantime, it will certainly take me some time to get used to it”.

nal take. My review of the opening of McBurney’s version included “In contrast to the previous production, this Magic Flute is dark, mysterious and more than a little weird. A flood of ideas drenched the stage, aided by a commentator sitting in a box in the corner, chalking up comments onto a large video screen. But there seems, at least to me, on first sight, little coherence to link it all together. Masonic references are played down, but the element of cult is still stressed through colour-coded camps in conflict . . . It may well be that, in 25 years time, I will miss this production. But, in the meantime, it will certainly take me some time to get used to it”. centred on the fascinating character Joseph de Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-George (b1745), the son of a wealthy French plantation owner in Guadeloupe, and his African slave. Educated back in France from the age of 7, he first became known as a fencer, graduating from the Academy of fencing and horsemanship aged 21 and somehow collecting the title of chevalier (knight) on the way. Quite how he achieved his skills in music is not known, but the composers Lolli and Gossec had already dedicated works to him before he was 21. He quickly became one of the leading Parisian violinists and orchestra leaders. He briefly lived in the same house as Mozart (the mansion of his mentor, the Duke of Orléans in Paris), and was leader of the enormous Masonic Loge Olympique orchestra, for which Haydn wrote his Paris Symphonies.

centred on the fascinating character Joseph de Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-George (b1745), the son of a wealthy French plantation owner in Guadeloupe, and his African slave. Educated back in France from the age of 7, he first became known as a fencer, graduating from the Academy of fencing and horsemanship aged 21 and somehow collecting the title of chevalier (knight) on the way. Quite how he achieved his skills in music is not known, but the composers Lolli and Gossec had already dedicated works to him before he was 21. He quickly became one of the leading Parisian violinists and orchestra leaders. He briefly lived in the same house as Mozart (the mansion of his mentor, the Duke of Orléans in Paris), and was leader of the enormous Masonic Loge Olympique orchestra, for which Haydn wrote his Paris Symphonies.