Death of Gesualdo

The Gesualdo Six, Owain Park, Concert Theatre Works, Bill Barclay

St Martin in the Fields, 16 January 2026

Billed as a “theatrical concert”, this follow-up to the 2023 Secret Byrd (reviewed here) featured The Gesualdo Six (director Owain Park) again pairing with Concert Theatre Works for a staged reflection on the life (and death) of the extraordinary madrigal composer, Carlo Gesualdo (1566-1613). Co-commissioned by St Martin-in-the-Fields to mark its 300th anniversary, The National Centre for Early Music in York and Music Before 1800 in New York City, this was the first performance before a short tour to York (Sunday 18 and Monday 19 January and New York’s St. John the Divine (Friday 13 February 2026. It was described as a “Stations of the Cross” for the composer’s tortured conscience, and sought to show “how the life and music of this enigmatic prodigy function”.

Probably most famous for murdering his wife and her lover in bed, Gesualdo, the hereditary Prince of Venosa, is revered for his wild experiments into advanced chromaticism, centuries before other composers began to explore the outer edges of harmonic theory. His tortured mind led to a life of violence and suffering, concluding in appalling tales of sorcery and flagellation. However macabre his biography, the theory of this production was that his character can be traced to key incidents from his upbringing in the world of Catholic politics.

The 2023 Secret Byrd was performed in the crypt of St Martin-in-the-Fields, a visually compelling setting, with action taking place in various locations. This performance was in the main church, which catered for a much larger crowd, but removed much of the intimacy. A raised stage helped people towards the back see what was going on, which can be an issue at concerts in the church. It was also a far more static performance, with the six actors (described as ‘dancers’) creating a series of tableaux, with much of the stage movement geared towards creating said tableaux. As we entered, Gesualdo was lying on his deathbed, dead or not far off it, with a couple alternating candle-holding duties. As the music started, the lights dimmed, and we reverted to scenes from his childhood, enacted over his prostrate body with a puppet, which later represented his dead son as he died again in real time.

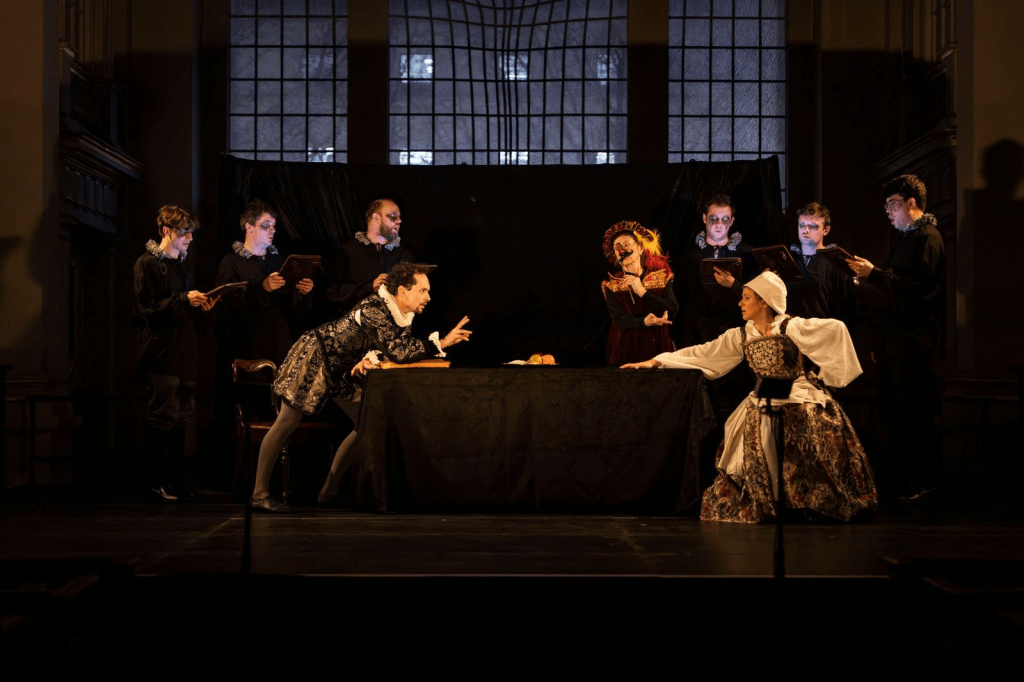

The six singers of The Gesualdo Six were on stage the whole time, dressed rather sinisterly in black monk-like habits and with unexplained black eyes. Singing from tablets, I rather liked the way that they entered, with the tablets pressed to their chest to reduce the glow from the screens (to various degrees) before tilting them forward so they, and we, could see them. As well as the glow from the tablets, they all had small, slightly larger than mobile phone-sized LED lighting blocks, which formed a key part of the lighting scheme, aided by ten similar lights on stands around the stage. Although a rather contrived device, it worked reasonably well to bring a Caravaggio-like feel to the tableaux. Incidentally, Caravaggio was an exact contemporary of Gesualdo, and I was surprised that there was no reference to him in the programme, given the rather obvious influence on the staging and lighting. Another ‘incidentally’ was the fact that there were no printed programmes, the audience having to scan a QR code on their mobile phones to access the programme. From where I was sitting, close to the front, hardly anybody actually bothered looking at their phones during the performance, which was no bad thing,

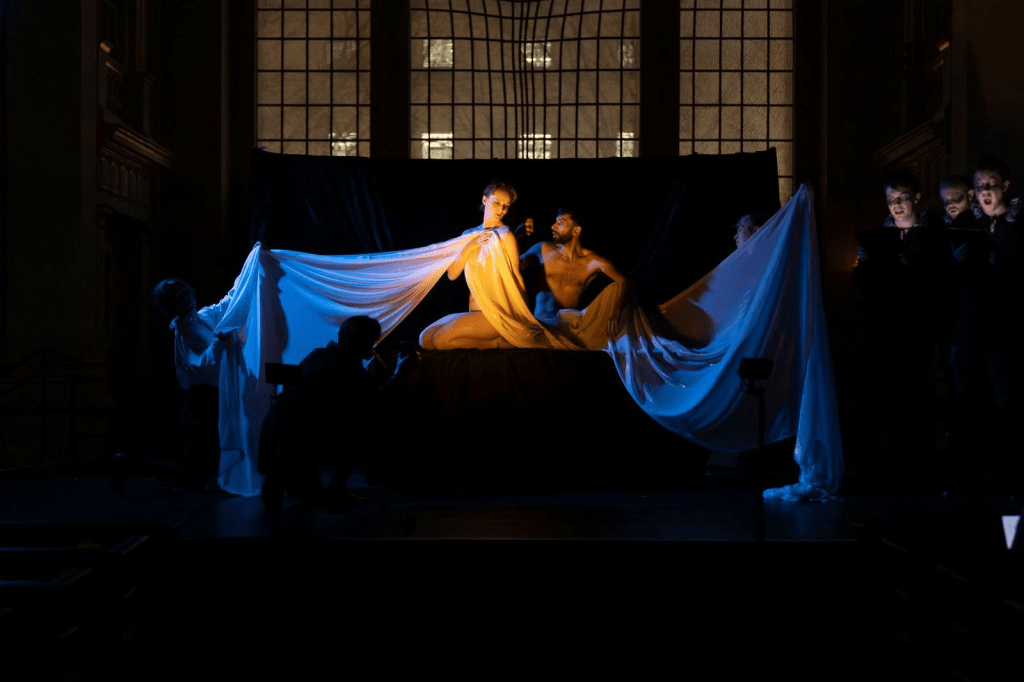

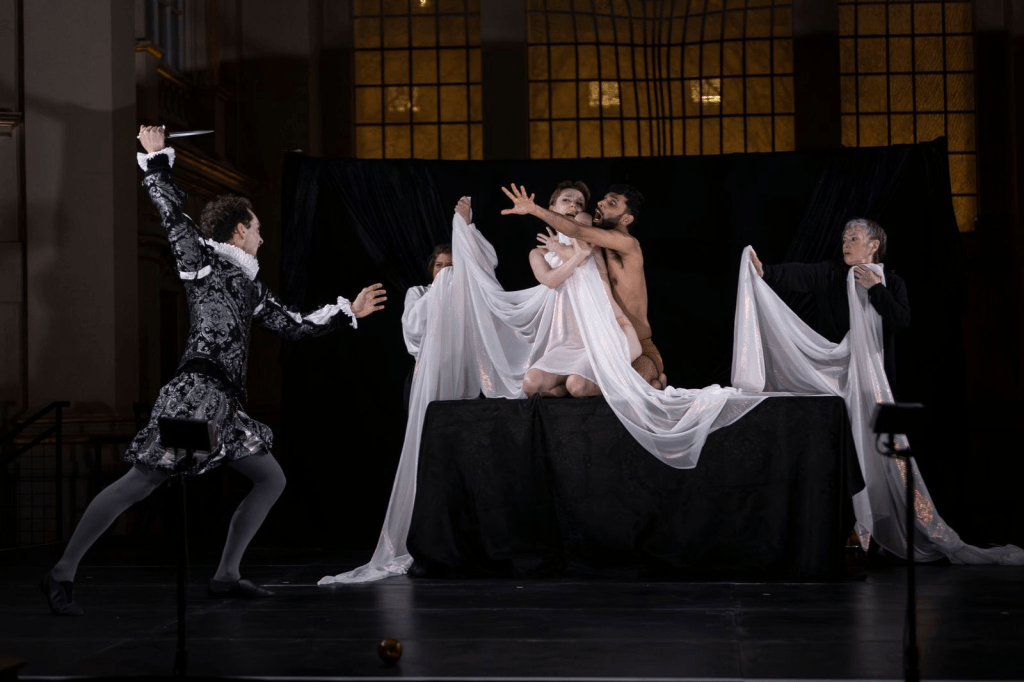

As the stage action moved through various aspects of his childhood, many of which were lost on me, one feature was a wooden cross/sword/air-guitar (or, more likely, an air-archlute). The only other props were large gauze veils, which feature in many of the scenes, most notably in the murder sequence (pictured below) when they first formed a degree of blue modesty to the seemingly naked actors, swapping for white for the actual murder scene, and blood red for the post-screaming aftermath.

The murder sequence. Markus Weinfurter, Imogen Frances and Taraash Mehrotra.

Although comedy was unlikely to have featured much in Gesualdo’s life, one little scene that might not have been visible to those towards the back was an actor/dancer wandering around with a quill pen, trying to write on the singers’ tablets. Unless you had more than a passing knowledge of Gesualdo’s life (and even if you did), much of what was portrayed by the actor/dancers is likely to have been rather confusing. It is difficult to know how they could have made the details of his life more apparent without losing the atmosphere of the event. Surtitles might have helped, but would inevitably take the eye away from the ‘action’, and the complexity of Gesualdo’s life is such that a narrator would take up the bulk of the evening. In it current incarnation, it was like wandering through the seventeenth Italian section of an art gallery, with headphones on!

For me, the stars of the evening were the singers of The Gesualdo Six and the music of Gesualdo, which, regardless of his life, is out of this world. I won’t go into the various theories as to how he achieved his weird harmonies, but I do like the notion that an enharmonic keyboard might have been involved in their composition. The singing was spectacular, the skill of the singers in keeping the harmonies tight, on pitch, and with perfect intonation. The music drew from Tenebrae, the mass Gesualdo wrote for his own death, together with madrigals from books 4, 5, and 6. The promotional video below gives an idea of the production.

Performance photos: Paul Marc Mitchell