Charpentier’s Actéon & Rameau’s Pygmalion

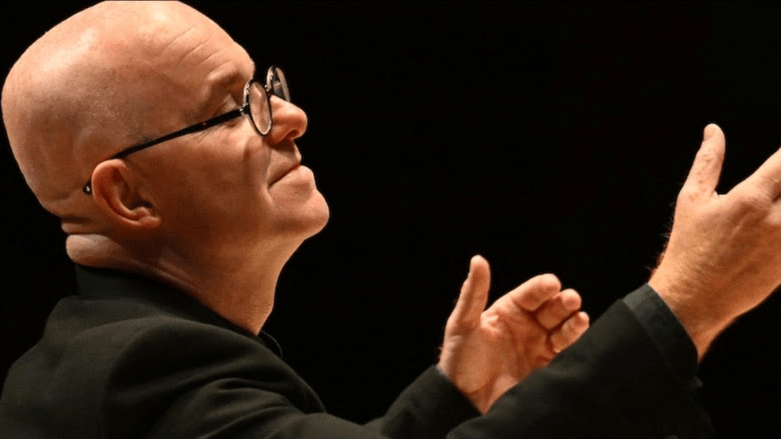

Academy of Ancient Music, Laurence Cummings

Anna Dennis, Rachel Redmond, Katie Bray, Thomas Walker

Milton Court, 9 October 2024

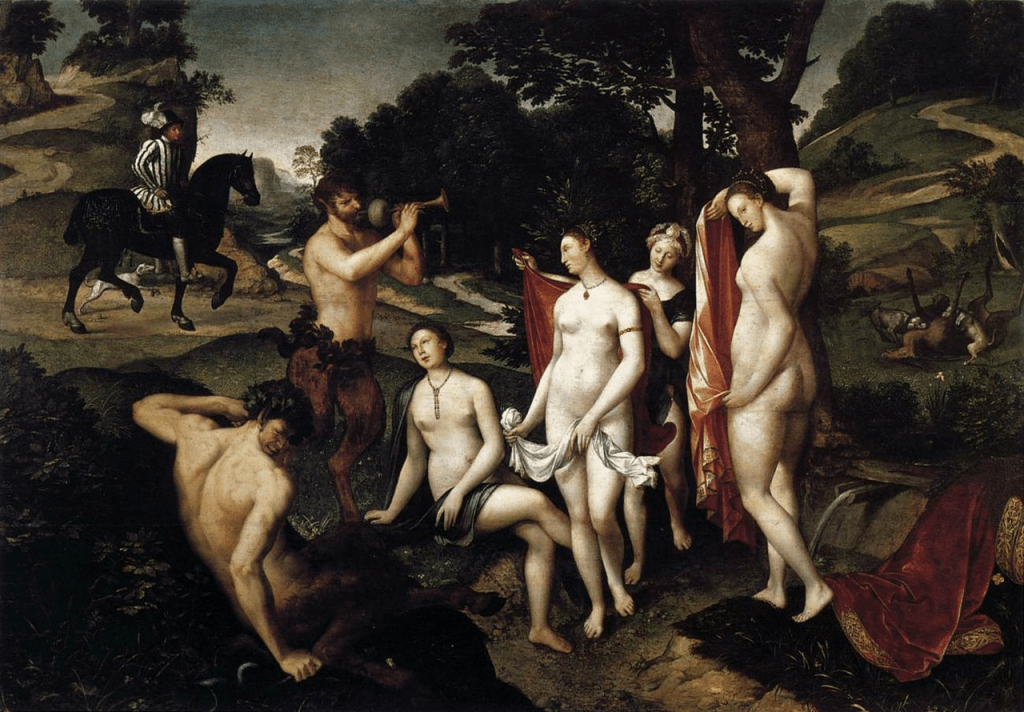

François Clouet: Bath of Diana (1558)

The Academy of Ancient Music opened its 2024/25 season, under the banner of Transformation, with a concert performance double-bill of French Baroque ‘operas’ or, more exactly, a Pastorale en musique and an Acte de ballet – Marc-Antoine Charpentier’s Actéon and Jean-Philippe Rameau’s Pygmalion. I am following those irritating promotional videos that encourage you to stay tuned until the end by urging you to read this review through to the end – this concert ended with one of the most extraordinary examples of musical professionalism and skill from the AAM’s musical director, Laurence Cummings, recently and deservedly appointed as an OBE.

Charpentier’s Actéon and Rameau’s Pygmalion present the theme of transformation in two very different, both based on the myths of the Roman poet and playboy Ovid (c43BCE–18CE) from his epic fifteen-volume Metamorphoses. This narrative poem outlines the history of the world from its creation to Ovid’s birth (and Julius Ceaser’s death), based on Greek myths and other folk legends.

Charpentier’s Actéon tells the story of a Thebian Prince who takes time out from a hunt to dream in a forest grove, only to realise that the goddess Diana and her two attendant nymphs have chosen to strip off and bathe naked in the nearby forest spring. Understandably, but unwisely, he approaches the spring but is discovered. Given the chance to explain himself, he offers a pathetic excuse whereupon Diana turns him into a stag. His fellow hunters return with their dogs who tear the ‘stag’ to bits. Juno descends from Olympus to explain that it was all her doing as a continuation of her jealous rage against her wayward husband, Jupiter, who has been having his way with Europa, a relative of the unfortunate Actéon.

It seems possible that Charpentier himself sang the haute-contra title role, his place this evening being taken by the impressive tenor Thomas Walker whose voice segued comfortably into that very French ‘high-tenor’ timbre. His extended pastorale sequence Amis, les ombres raccourcies as he lays down to rest and his later Mon coeur autre fois intrépide as he sees his reflection as he is transformed into a stag were vocal and musical highlights. The small band produced some delightful colours from pairs of violins (Bojan Čičić & Persephone Gibbs), flutes/recorders (Rachel Brown & Maria Filippova) and oboes supported by a continuo group of Reiko Ichise, viola da gamba, William Carter, theorbo and Laurence Cummings sensitively directing from the harpsichord.

Rodin: Pygmalion and Galatea

In Rameau’s Pygmalion, a sculptor falls in love with his own statue, to the understandable anger of his girlfriend Céphise, here sung by mezzo Katie Bray who had earlier taken the role of the spurned Juno in Actéon. Thomas Walker offers a slightly better excuse as Pygmalion as he did as Actéon, blaming the gods. Soprano Anna Dennis moved from her more active role of Diana to that of the statue, sitting motionless front-stage until her own transformation. Rachel Redmond, previously Arethusa in Actéon, was now Amor, completed the line-up of excellent soloists. Amor is kinder to Pygmalion than Diana was to Actéon, granting his wish for the statue to come to life, and introducing a delightful sequence of dances (helpfully detailed in the surtitles) as the Graces teach the statue to dance before the concluding scene where Pygmalion and ‘the people’ praise the irresistible power of Love in L’Amour triomphe, annoncez sa victoire.

An already memorable concert finished with one of the most extraordinary examples of musical professionalism and skill I have witnessed

During the sequence of Pantomime dances, all singers having left the stage, an unknown figure entered and whispered in Laurence Cummings’ ear. As the (much enlarged) band set off for Pygmalion’s concluding Règne, Amour, fais briller tes flammes, there was no sign of Pygmalion, tenor Thomas Walker seeming to have suffered some sort of off-stage vocal malfunction. Instead, as if it was all part of Rameau’s score and a perfectly normal thing to do, Laurence Cummings picked up his large conducting score, turned to the audience, transformed himself into Pygmalion, and sang the virtuoso concluding aria himself in an impressive haute-contra voice while giving conducting hints to the band who were now behind him. I have known for many years how fine a singer Laurence Cummings was, but this was an astonishing feat, not only of singing some of the hardest and most flamboyant passages of the whole evening but quite possibly singing it for the first time out loud, rather than in his head. Thomas Walker appeared for the applause, giving Laurence Cummings a well-deserved hug. If that doesn’t speed his way to his transformation to a CBE, I don’t know what will.