St Matthew Passion

Academy of Ancient Music, Laurence Cummings

The Barbican, 29 March 2024

The Academy of Ancient Music (an Associate Ensemble at the Barbican Centre) is celebrating the 50th anniversary of its foundation by Christopher Hogwood. At a time when practically everybody else was concentrating on the St John Passion, in its anniversary year, they promoted a special performance of the Matthew Passion in the Barbican Hall, directed by their Music Director, Laurence Cummings. What was special about it was that they took the music back to its Leipzig roots, with a small orchestra (or, to be exact, two small orchestras) and a choir of just 8 (4+4) singers, all of whom contributed solos (of various importance), including, in Choir 1, the key roles of the Evangelist and Christus and the multi-character bass in Choir 2.

Whether or not this is what Bach intended is open to discussion, not least because there is a reasonably sound theory that Bach may have reinforced the solo singers with additional singers for the chorus, of which there are three major ones and several important short interjections. But here, it certainly worked. The Barbican Hall is far from an ideal space for this sort of performance, with its wide stage and wider-spread audience. The decision to place the singers behind the orchestras was an ‘interesting’ one that might have given them a more understanding acoustic to sing into but reduced the visual impact for those listening in the hall, notably in removing the intimacy of Nicholas Mulroy’s outstandingly moving and communicative story-telling as the Evangelist.

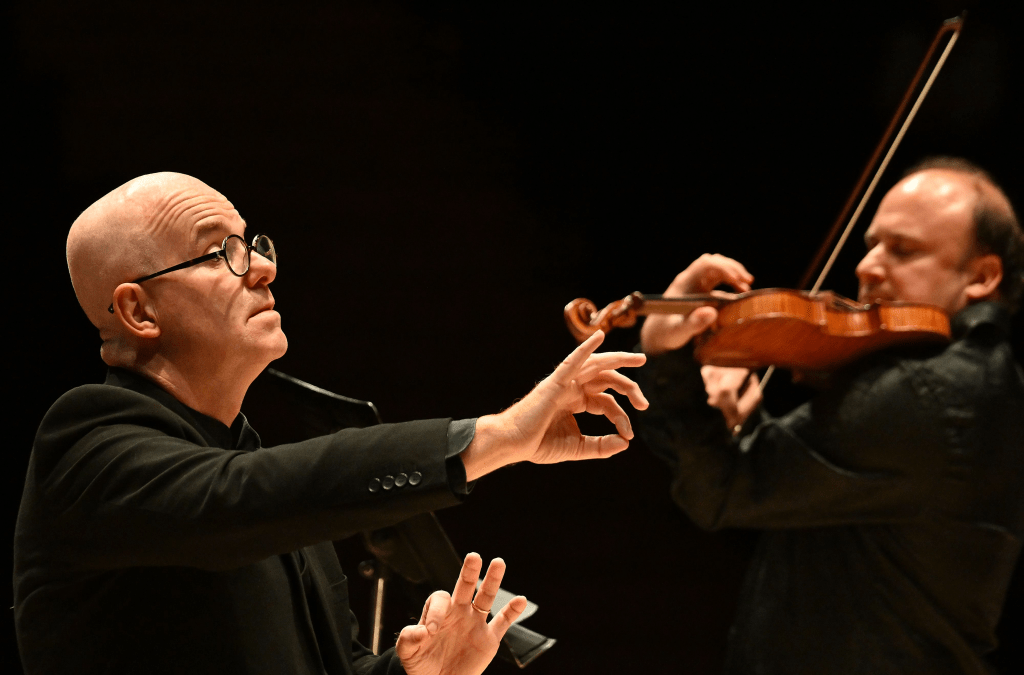

The opening chorus for the combined forces was useful in introducing the audience to the highest volume they would expect. In a full-blown orchestral concert, this would be rated at no more the a mezze-forte, but here, helped by some delightful shading of tone and texture from conductor Laurence Cummings (recently and well-deservedly, OBE’d), the focus was on the clarity of individual lines and the interplay of contrapuntal lines. An unnecessary pause for latecomers was an unfortunate lapse of momentum, with the Barbican’s expected signal to the conductor to continue clearly not working. But from then on Cummings kept the pace going at, for him, a relatively sedate pace. This avoidance of excessive speeds, which Cummings (picture below, with the AAM leader, Bojan Čičić) can excel at in the right music, helped to emphasize the contemplative nature of the music and the way that Bach unfolds the complex drama.

Nicholas Mulroy was the star of the show, at least for those who didn’t assume that was Jesus. Vocally, and as far as I could see, facially, he led us through the vast range of emotions with extraordinary sensitivity. Amongst the many telling moments, the most emotive was his heartwrenching pause before the brief “und verschied” (“and died”), an audience cough being particularly badly timed. His recitative and aria O Schmerz! / Ich will bei meinem Jesus wachen”, was very moving, with its interplay between tenor soloist and Choir 2 combined with elegant oboe playing from Robert de Bree. This was one of the moments when some very effective little improvised twiddles were added, both from the oboe and Laurence Cummings’ organ continuo accompaniment.

As well as a central harpsichord, there were two organs, the smaller one used by Laurence Cumming on the Choir 1 side, facing towards the performers, the larger one, played by Alistair Ross, on the Choir 2 side, facing forwards diagonally across the stage. It might have been different from the side of the hall the larger organ faced, but from where I was sitting the key choral melody of the German Agnus Dei O Lamm Gottes unschuldig in the opening chorus Kommt, ihr Töchter, helft mir klagen was barely audible. It is likely that in the Leipzig performances, the choral would have been played on a distinctive (probably Sesquialtera) registration on the main west-end church organ, which would have had the two choirs and orchestras on either side of it. In later versions, this melody was sung by a ripeano choir.

The principal vocal soloists were Anna Dennis, Tim Mead, Nicholas Mulroy, George Humphreys (a solid portrayal of Christus) from Choir 1 and Rodney Earl Clarke from Choir 2 singing the bass roles of Judas, Peter and Pilot with impressive tone and variety between the personalities. Anna Dennis and Tim Mead were a fine pairing in So ist mein Jesus nun gefangen with the combined choirs making a bold entry on the contrasting Sind Blitze, sind Donner bit. However, Anna Dennis was a trifle dominant in some of the chorus passages, at least from my seat.

Amongst the instrumentalists, special mention is deserved by violinists Bojan Čičić and Julie Kuhn, continuo cellis Joseph Crouch with bassist Timothy Amherst, Orchestra 2 cellist Sarah McMahon, Reiko Ichise for her playing of the tortuously complex viola da Gamba accompaniment to the aria Komm, Komm, süßes Kreuz,

One programme hiccup that might have confused those following the text was that the end of Part 1 was shown as being the choral Jesum lass ich nicht von mir which was the case in the early (1727) version, but that performed the chorale fantasia O Mensch, bewein dein Sünde groß as used in later versions of the Passion.

I am, not an expert on such things, but I would imagine that at 3pm on Good Friday devout Christians are likely to be in their own church, or perhaps at a Bach Passion in a church as part of a service (including, of course, the sermon that in Bach’s day would have taken place between the two parts of the Passion). That raises the question of how many of the audience (or, indeed, the performers) were true believers in the Christian Easter story. I am not, but the only aspect of that which affects my enjoyment of the Passions is that the Matthew Passion does go on a bit, particularly with the final series of recitatives. As far as following what was going on, I have far more trouble understanding the equally unbelievable plots of many operas.

Amongst issues that the Barbican needs to sort out (notably the appalling state of their loos), the arrangements for the 6pm Fountain Room pre-concert talk is one. All the seats were taken by 5.45, the standing places filled by 5.50 and a large and restless crowd denied entry under room capacity instructions. Whether legal or not, some sort of arrangement was finally achieved allowing most of them to enter and stand at the back.