Johann Sebastian Bach: Two organ Chaconnes

Ciacona ex d BWV 1178, Ciacona ex g BWV 1179

Ed. Peter Wollny

Supplement to Bach Complete Organ Works, Volume 4

24 pages, 32x23cm, 137g, ISMN: 979-0-004-19141-5, Saddle Stitch

Edition Breitkopf 9648, 2025

The much hyped promotion by the Bach Archive Leipzig of two organ Chaconnes that have recently been attributed to the young J.S. Bach has resulted in a torrent of internet posts raising every possible view of the music and how it should be performed. This commenced with the first performance of the new attributions given by Ton Koopman, playing the 2000 Bach organ at an official ceremony on 17 November 2025, livestreamed from Bach’s own Thomaskirche Leipzig. The two pieces have been available for a while on IMSLP, in facsimile and typeset, under the tentative attribution to Johann Christoph Graff. They are now published by Breitkopf in an edition by Peter Wollny, director of the Bach Archive Leipzig and the scholar who attributes the two pieces to JS Bach. A detailed Preface in German and English (four pages each) outlines the voyage of discovery over a period of more than 30 years. The new Breitkopf edition of the two pieces is beautifully produced and presented, with clear musical text.

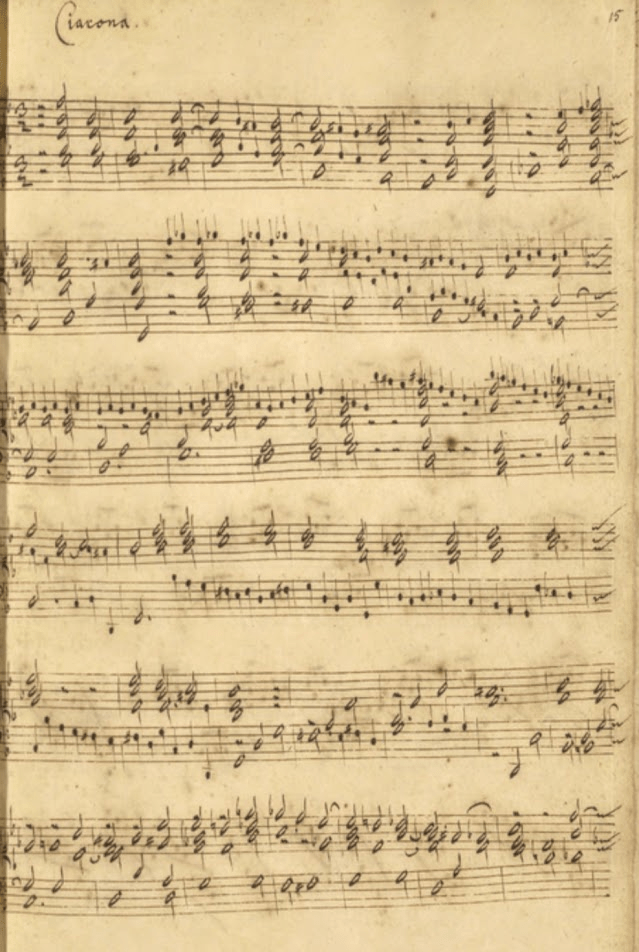

The two pieces are found in a single source in the Bibliothèque royale de Belgique in Brussels (B-Br Ms II 3911 Mus (Fétis 2013)). They are preserved in a manuscript from the Fétis collection, compiled by the musicologist and composer François-Joseph Fétis, the first director of the Royal Conservatory of Brussels. A digitised version of the complete manuscript can be viewed here. Twenty-five pieces by Sorge, Fosel, and Kellner are preceded by six chaconne movements, two by Pachelbel and one by JC Graff. The last two of these six chaconnes have now been attributed by Peter Wollny to JS Bach, based initially on his conviction that the writer of the Fetis manuscript was Salomon Günther John.

Ciacona ex d, BWV 1178

Bibliothèque royale de Belgique (B-Br): Ms II 3911 Mus (Fetis 2013)

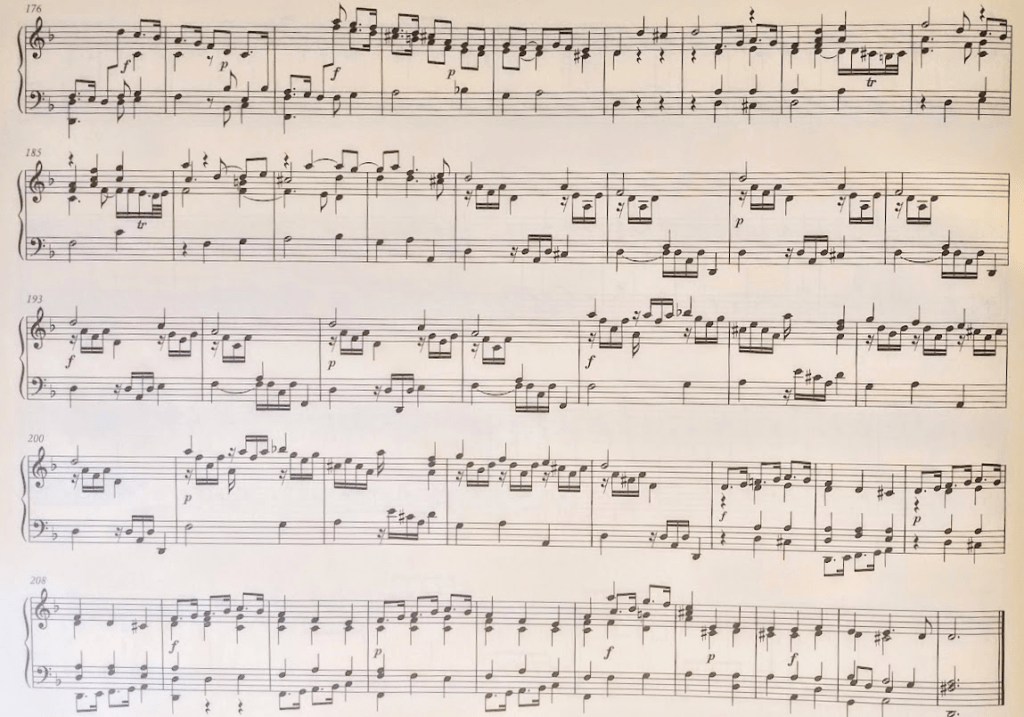

For some reason, in both the Royal Conservatory of Brussels digitised version of the complete manuscript and the same version on IMSLP, the Ciacona ex d breaks off partway through the fugal section (at bar 117 in the Breitkopf edition). The next page is the start of the Ciacona ex g. There is no reference to this in the published edition or, as far as I can tell, elsewhere, but the rest of the fugue and the return of the Ciacona certainly exists as it appears in Ton Koopman’s highly ornamented and rather quirky performance, here, which has a scrolling score from the John manuscript, complete with the missing bars. In one of the two transcribed versions on IMSLP, the fugue ends with a fermata, two rests to complete the bar, and a da capo indicating a return to the initial Ciacona. The other one omits the rests, implying a direct return to the Ciacona. This is the approach sensibly adopted in the Breitkopf edition, where the fugue merges directly into a written-out repeat of the opening Ciacona, without the repeat marks of the initial Ciacona.

Ciacona ex g, BWV 1179

Bibliothèque royale de Belgique (B-Br): Ms II 3911 Mus (Fetis 2013)

Salomon Günther John was born in 1695 near Arnstadt and was arguably a student of Bach in Arnstadt. John does not actually name Bach, but stated in 1727 that he had “initially studied with the former organist in Arnstadt” and had subsequently worked “in the Grand Ducal Chapel in Weimar”. By process of elimination of the eight or so possible candidates as the ‘former organist in Arnstadt’, Bach is the most obvious choice. Wollny’s analysis of John’s handwriting, which includes examples from his youthful Arnstadt years, reinforces the link with the music in the Fetis manuscript to John’s time in Arnstadt. The link in Weimar is slightly more tenuous, as there is no record of him there, but it is possible that he was one of the chapel boys in the castle chapel during Bach’s time. Based on his handwriting analysis, Wollny suggests that the two pieces were written during Bach’s time in Arnstadt and that “strong evidence even suggests Bach’s authorship.”

Having placed the manuscript to Bach’s time in Arnstadt, the next key question is whether the music was actually composed by Bach. Wollny’s argument for this attribution is based mainly on stylistic grounds. For the Ciacona ex d BWV 1178, its structural complexity and unusual moments departing from the style of chaconnes at the time, one being the inclusion of a fully worked fugue in the middle of the D minor Chaconne, the only other known example being Bach’s famous C minor Passacaglia BWV 582, where a fugue follows the Passacaglia. Wollny recognises in the echo effects a possible link to the music of Georg Böhm that Bach probably knew during his school days in Lüneburg (1700-1702). Based on the pioneering studies of the early years of Bach by the distinguished Bach scholar Jean-Claude Zehner (the dedicatee of the Breitkopf edition), Wollny suggests that BWV 1178 could have been composed as early as 1701, possibly in Lüneburg, under the direct influence of Böhm.

The Ciacona ex g BWV 1179 has a similar seven-measure ostinato to BWV 1178, but treats it to much wider rhythmic and harmonic variability, including transposed form. Specific links to other Bach works are noted, notably the chaconne at the end of cantata BWV 150, composed in 1707. Wollny sees the Ciacona ex g as an “early sister piece” to BWV 150 with a suggested dating of 1703/4 during the early Arnstadt years. The arpeggio passages also suggest (to me, at least) links with the C minor Passacaglia BWV 582.

Last page of Ciacona ex d, BWV 1178. Breitkopf edition 9648

Since the announcement on November 17, numerous performances of the Chaconnes, of varying quality, have appeared online, many played on Hauptwerk organs in living rooms. One powerful Hauptwerk version of BWV 1178, from Ralph Looij, can be heard here, with a scrolling score taken from the IMSLP transcription where the fugue ends with a fermata and two rests to complete the bar before the da capo and with repeats in the da capo. One performance of both pieces that I found particularly attractive can be found here, played by Andrew Dewar on a 2007 Dominique Thomas chamber organ (nicknamed Josephine), currently on loan to the American Cathedral in Paris. In this performance, the Ciacona ex d lasts about 9 minutes (in comparison to Ton Koopman’s 7 minutes), and the Ciacona ex g, 4’30” (Koopman, 3’25”).

In conclusion, I am convinced that the attribution of the writing to Salomon Günther John is correct, and accept that JS Bach was almost certainly the “former organist in Arnstadt” that he studied with. As to whether Bach was the composer, the arguments are convincing, although stylistic arguments are always open to discussion and possible review. The potential link to Georg Böhm in Lüneburg is certainly appropriate. The Bach connection is already accepted, not least because of CPE Bach’s comment that his father “loved and studied” the works of Böhm. One of the earliest known Bach manuscripts is a copy of a piece (by Reinken) that Bõhm owned. A Böhm link would explain the hint of French style in the larger-scale Ciacona ex d, BWV 1178. Böhm was familiar with French (and Italian) music from his pre-Lüneburg time in Jena and Hamburg (Lully operas were frequently performed at the Hamburg opera, directed by a Lully pupil), and also because of the importance of French music in several of Lüneburg’s nearby courts, including Celle and Hanover. Even if it is later proved that these pieces are not by Bach, the exposure that they will get in the meantime is well worthwhile. There are vast numbers of similarly impressive but anonymous organ pieces from the 17th and early 18th century, but fear of playing to an audience of about three has prevented me from making a feature of them in recital. One day . . .

As a postscript, here are a few random and anonymised quotes.

“I still think they are not Bach. Firstly, he wasn’t that skilled a composer at 18; secondly, they have no North German traits and are much more aligned with South German music. I still think it’s Muffat or someone close to his circle. If we play them as would a French orchestra, with double dotting and then try to ease back into Germanic counterpoint and Italianate (dunno what, I’m drunk), then we have the Muffat playbook: a mixture of styles. This was not a Bach thing: when he came to style, he was the assimilator, but not terribly effective — ever — at synthesising a mixture of different elements (JF Dandrieu was the best at that).”

“Who am I to say these are or not by Bach? But still, my first impression was that these are by Muffat or Krieger. Krieger’s Giacona in g minor or Muffat’s Passacaglia in g minor is a great model. Pachelbel is also possible, and when you consider Böhm’s Chaconne in G major then I think Böhm is also possible. I wouldn’t go so far as to claim that Bach Archive Leipzig’s claims are a scam, but I do think the claims are somewhat questionable. At any rate, these are nice pieces. And if we believe that Salomon Günter John really compiled the manuscript under Bach’s supervision, then at least Bach would have known these pieces well, no?”

“Stylistic considerations apart, couldn’t Bach have asked John to copy a folder of music whose contents included some anonymous pieces not composed by Bach?”

“Well, it doesn’t sound like Bach to me, and it doesn’t look like Bach on the page either, but I know less than the square route of sod all”

One rather blunt comment on Ton Koopman’s performance is possibly worth mentioning:

“Utter rubbish! Can’t stand his playing and his over articulation and ridiculous ornamentation makes everything sound the same. A complete waste of time listening to him; there are plenty of other good performances online.”

The same writer commented on the presentation by Peter Wollny with a rather unpleasant “Zzzz“!