“Immortal Harmony”

London Festival of Baroque Music

Arcangelo, Spiritato, Les Demoiselles Couperin,

Choir of New College Oxford, Ensemble Marguerite Louse Versailes,

Smith Square Hall, 1, 7 & 8 November 2025

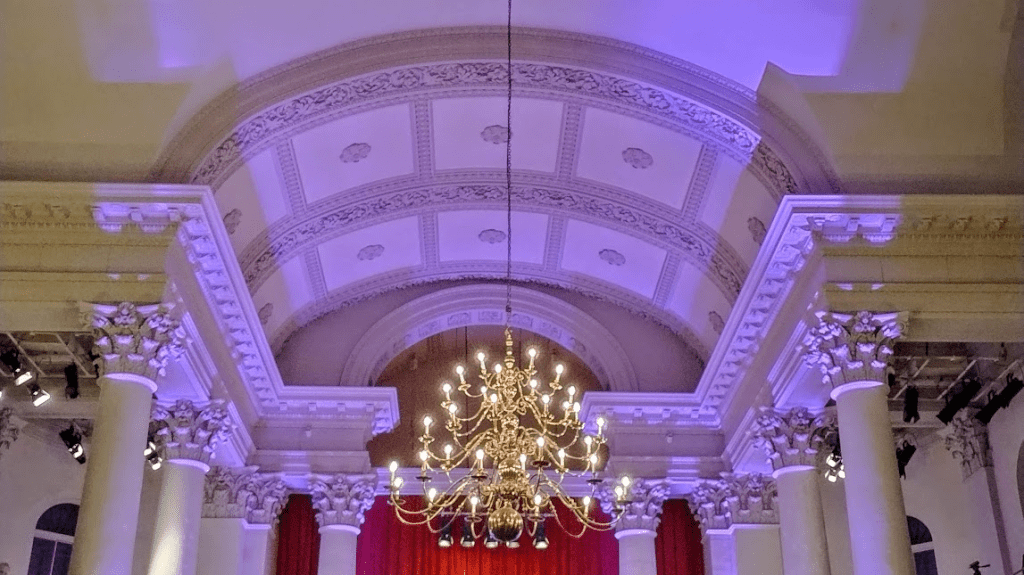

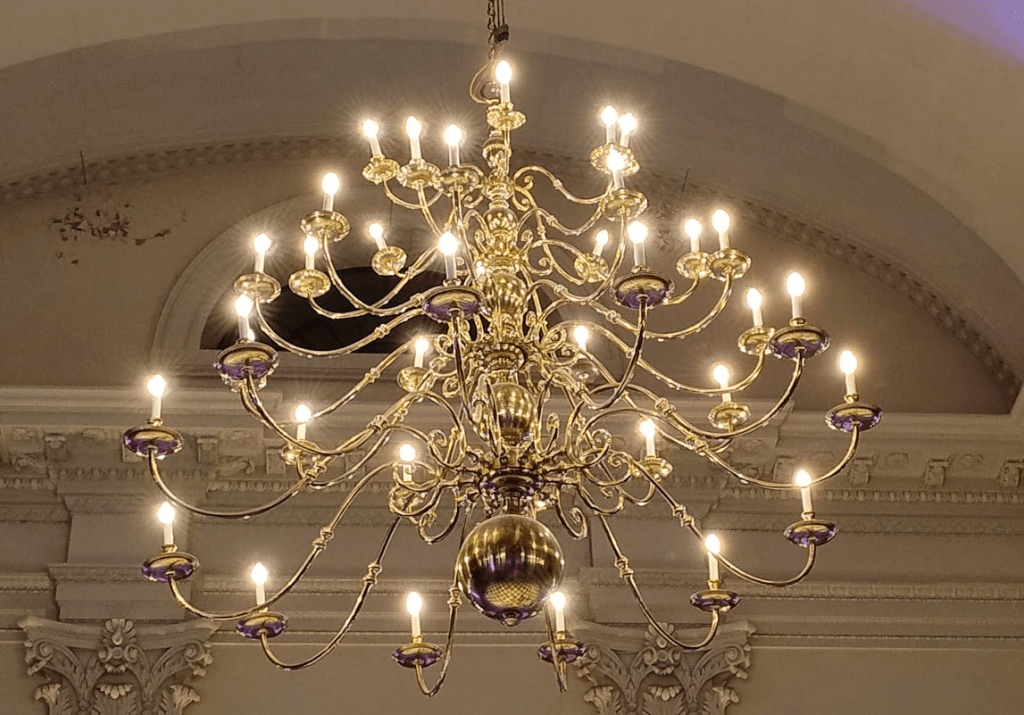

The London Festival of Baroque Music was founded in 1984 as the Lufthansa Festival of Baroque Music by conductor Ivor Bolton and musicologist Tess Knighton, its Artistic Director until 1997. Kate Bolton was Artistic Director from 1997 to 2007, succeeded by Lindsay Kemp. The first concerts took place at St James’s, Piccadilly, before settling into the fine Baroque church of St John’s, Smith Square, now renamed variously as Smith Square Hall or Sinfonia Smith Square. This year’s festival was given the overall title of “Immortal Harmony”. I attended the first and final three concerts, featuring Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos, Bach’s Leipzig legacy, vocal music by Couperin, and ceremonial music by Purcell, Lalande, and Charpentier.

The opening concert of the festival was given by Arcangelo, directed from the harpsichord by Jonathan Cohen (pictured below) with all six of Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos, albeit, for some unexplained reason, performed in reverse order, a seemingly last-minute change announced from the stage. The collection was put together in 1721 and presented, in autograph, to the Margrave of Brandenburg-Schwedt as Six Concerts Avec plusieurs Instruments. Based on documentary and stylistic evidence, several were probably composed earlier. It is unlikely that they were ever performed in their final form, not least because the Berlin court did not have the required wide range of instrumentalists. The 17 musicians in Bach’s own orchestra at Köthen could have performed the set, and may have performed the 5th concerto with its expansive harpsichord solos, to celebrate the arrival of a new harpsichord in 1719.

Playing them in reverse order resulted in the evening starting quietly and finishing with drama. I can understand that, but it was not what Bach intended. Showing disrespect to Bach’s intentions is a tricky enterprise, and it didn’t work for me. Apart from anything else, it radically reduced the effect of the 5th concerto with its possible subtext of the harpsichord player (probably Bach himself) fighting his way out of the shadows after playing continuo for the four previous concertos. That said, the performance was impressive, with some impressive playing.

The 6th concerto, which opened the concert, is a meditative affair, played with two violas (violes da braccio), two violas da gamba and continuo (here cello, bass, theordo and harpsichord). The continuo theorbo was far too prominent for my taste, not least by adding additional melody above Bach’s polyphonic lines. Lovely as it is in forming a relaxed conclusion to the five previous concertos, it is really not the sort of thing that would impress a Prussian prince at the start of a sequence of six concertos.

The virtuosic solo harpsichord role for the famous 5th concerto was handed to Tom Foster, who provided a musically sensitive interpretation of Bach’s flood of notes. The 4th concerto uses a solo violin and a pair of recorders (flauti d’echo), the violin having some particularly tricky moments. After the interval, we had the 3rd concerto, played by trios of violins, viola and cellos, with a continuo harpsichord and bass. The three violins stood in a line away from the audience, with the violas facing the audience and the cellos at an angle, but visible to the audience. This arrangement unbalances the sound from the 2nd and 3rd violins, giving undue prominence to the first violin, who is just one of several soloists. The 2nd concerto features the initially unfeasible solo combination of trumpets, oboe, recorder and violin. Although Bach cleverly provides perfect balance with the instruments, his judgment does rely on players not overdoing the volume, which the trumpet player did on this occasion – as, again, did the theorbo player. I can only assume that rehearsal time was very limited, as these sorts of balance issues really should have been resolved before the concert.

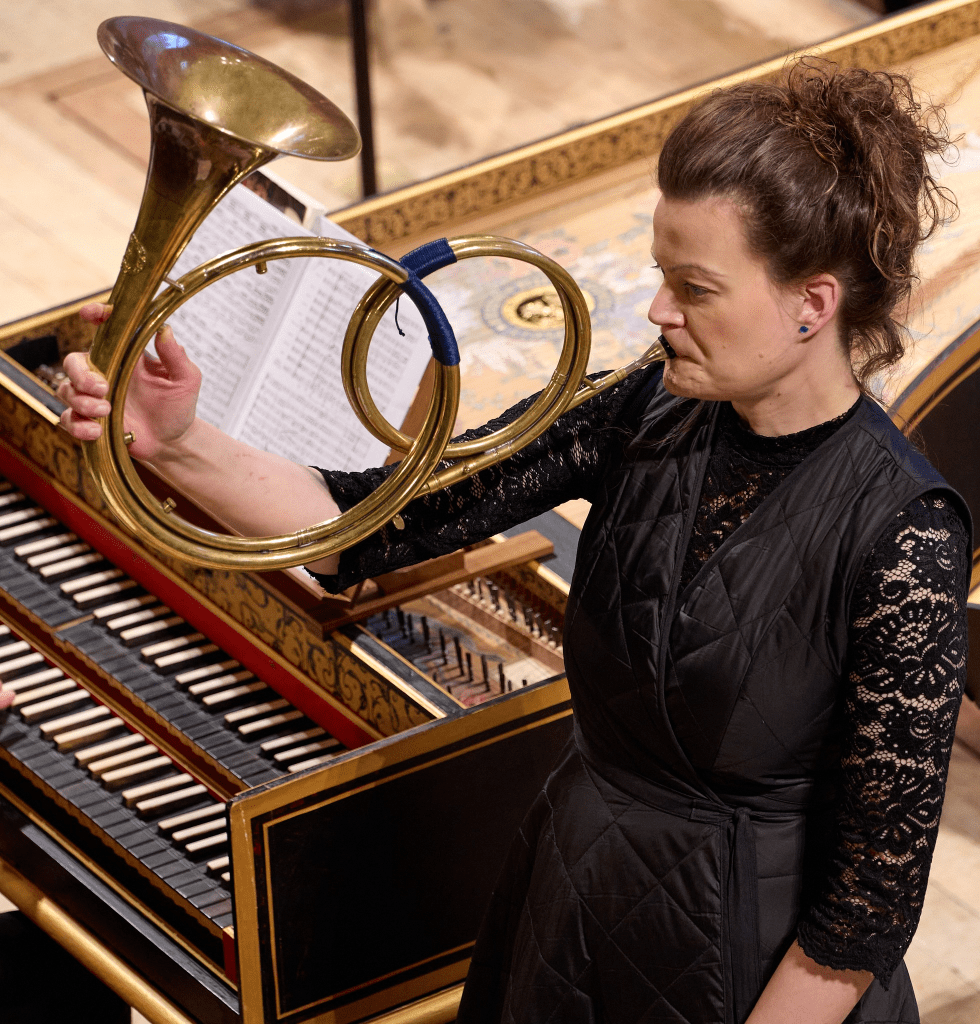

The final concerto was the first of the set, a dramatic piece obviously intended to impress the Margrave, if he was ever to hear it. It features two hunting horns (here played, as seen in the photo of Ursula Paludon Monberg, in what I am tempted to describe as an ‘erect’ position), alongside three oboes, bassoon and violin soloists.

The programme note was rather lazily taken from a ten-year-old American programme note website, and was curious, not least in mentioning an American TV show with the unlikely promise that many listeners would recognise the theme tune!

With their programme The Leipzig Legacy, the excellent group Spiritato, directed by violinist Kinga Ujszászi, gave an insight into the 1723 appointment of Bach as Kantor of the Leipzig Thomaskirche. Music by Bach wad contrasted with two of the composers who were in serious contention for the post before it was eventually offered to Bach. Christoph Graupner and Telemann were both offered the post before Bach, but both turned it down. Johann Friedrich Fasch had turned the post down the previous year. Sensibly avoiding the well-known Telemann, they concentrated their programme on Bach, Fasch and Graupner.

Fasch: Concerto in D major for 3 trumpets, timpani, 2 oboes, violin and strings

Bach: Orchestral Suite No. 2 in A minor (Early Version), BWV 1067

Graupner: Overture Suite in D major, GWV 420

Bach: Sinfonia in D major, BWV 1045

Fasch: Sonata in D minor for 2 Violins, Viola & B.c FWV N:d3

Bach: Orchestral Suite No. 3 in D major, BWV 1068

The opening Fasch Concerto was a lively three-movement piece, its rather martial style helped by three trumpets and timpani alongside violin, oboes, bassoon and strings. He had studied with Kuhnau, Bach’s predecessor at the Leipzig Thomasschule, and with Graupner, his prefect in the school. He was much travelled and held key appointments in Prague, Dresden and, succeeding Bach, in Köthen. He was influenced by Vivaldi, and composed in the genial galant style, a bridge between the Baroque and early Classical style.

The Bach A minor Orchestral Suite is argued by the American musicologist Joshua Rifkin to be an early version of the B-minor Orchestral Suite (BWV 1067), but with the violin as the solo instrument rather than the flute of the final version. He also suggests that it was inspired by a similar piece by his cousin, Johann Bernhard Bach. Like Fasch, Graupner studied with Kuhnau and taught the younger Fasch. After a period in Hamburg, where he played alongside Handel, he settled in the Court at Hesse-Darnstadt. He wrote many instrumental suites or overtures. After the opening French-style overture and fugue, GWV 420 has six other movements, including a Rejouissance, Air, Tombeau, and a concluding March. It is a lively and colourful sequence of pieces, with trumpets playing throughout and key solo moments for violin and oboe (Kinga Ujszászi and Joel Raymond).

The second half of the programme focused on Bach and Fasch, opening with Bach’s Sinfonia in D major, BWV 1045, a fascinating work composed in the 1740s in Leipzig, so comparatively late in Bach’s composing career. It was intended for a now-lost Cantata, which must have been of a particularly celebratory nature, given the scale and power of the Sinfonia. It could also pass as a movement of a violin concerto, given the exceptionally complex violin writing. It was followed by Fasch’s chamber Sonata in D minor for 2 Violins, Viola and continuo: a lovely example of his more domestic pieces.

The concert finished in more familiar territory with the Bach Orchestral Suite No. 3 in D major. The earliest autograph copy of this is written in the hands of Bach (1st violin and continuo parts), his son, CPE Bach (trumpets, oboes, and timpani parts), and his student Krebs (2nd violin and viola parts), an interesting insight into the Bach household musical factory. Spiritato’s powerful performance was helped by a sensibly-paced and suitably Baroque version of the famous Air, helping to contrast the dramatic intensity of the other movements. An excellent concert.

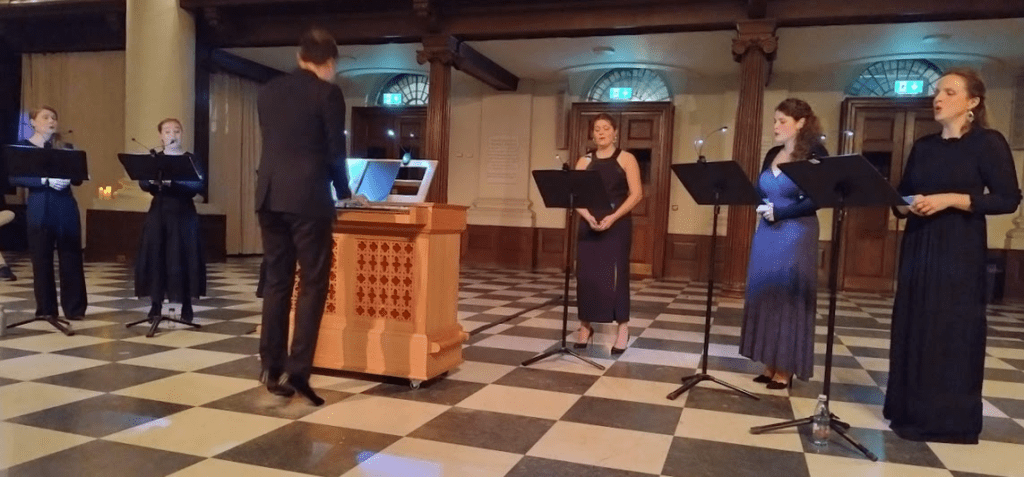

A late concert on the same Friday evening was given by six strong all-female Les Demoiselles Couperin (The Couperin Ladies) and was, appropriately, devoted to François Couperin. They were formed as a tribute to the first women permitted to sing at the gallery of the Royal Chapel of Versailles, transforming sacred music in the process. They are directed by Gaétan Jarry, currently organist at the extended Couperin family’s church of Saint-Gervais, which still contains an organ dating back to Couperin’s time. The programme was a sequence of motets, a Magnificat and the Troisième leçon de ténèbres (composed for the Abbaye de Longchamp). Originally for two female voices, they were here arranged for six sopranos, two of whom had significant solo roles.

I had a couple of concerns over this concert, one being the distracting and inelegant physical antics of the director, the other being the excessive vibrato of one of the two soloists: something I find particularly problematic in French Baroque music, with its plethora of ornaments.

The festival finished on Saturday 8 Novemeber with Royal Farewells and Triumphs, a grand event combining the Choir of New College Oxford and Ensemble Marguerite Louse Versailles orchestra, the latter making its UK debut, helped by an impressive body of sponsors. They gave a programme of English and French music directed in turn by Robert Quinney and Gaétan Jarry.

Henry Purcell: Music for the Funeral of Queen Mary, Z. 860

Michel-Richard de Lalande: De Profundis, S. 23

Henry Purcell: My Heart is Inditing

Marc-Antoine Charpentier: Te Deum, H. 146

It was a fascinating programme, and an interesting insight into musical international relations, with English singers singing French music and a French orchestra accompanying English music. Fairly early into a new term, the Choir of New College Oxford has had limited time to settle in, but revealed no issues; the boys, some looking very young, produced a fine ensemble sound. The opening Purcell featured Yoav Gal, a particularly impressive pure-toned treble soloist with a commendable grasp of Purcellian ornamentation. The other treble soloists later in the programme, Jack Baker-Ellis, Theo House, and Felix Thorpe, were similarly impressive.

The adult soloists, either drawn from the student choir or invited in, also impressed. One exception was a singer listed as a French-style haute-contre, but singing as a countertenor (a voice type not appropriate for the French repertoire), whose continuous strong vibrato was a major disruption. The accompaniment of the Ensemble Marguerite Louse Versailles was particularly effective in the opening Purcell, with continuo support from three violas da gamba, two cellos, bass and organ.