Laus Polyphoniae 2025

Ars Antiqua – Ars Nova – Ars Subtilior

Polyphony from the age of cathedral builders (1140-1440)

Antwerp, Flanders

22 August – 31 August 2025

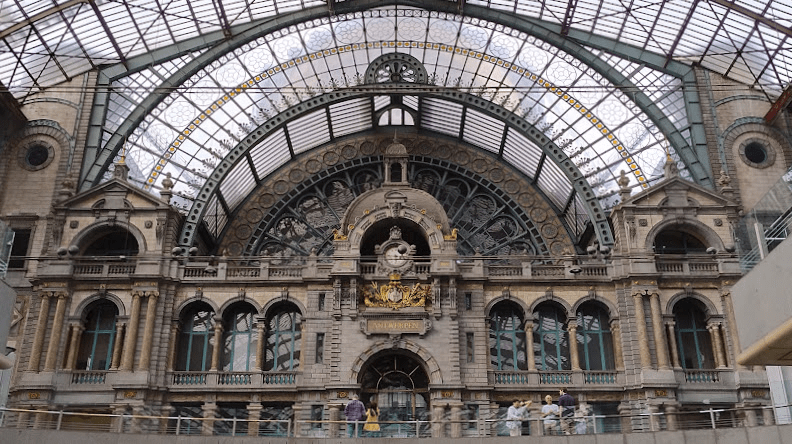

Laus Polyphoniae is the annual festival organised by AMUZ (Flanders Festival Antwerp), dedicated to the music of the Middle Ages and Renaissance era. Since its inception in 1994, the festival has grown to become the largest festival dedicated to the European heritage of polyphony. The rebirth of Notre Dame in Paris following the fire was an ideal moment to explore the musical heritage of Europe’s cathedrals – architectural masterpieces that sparked a revolution in music. Under the title of Ars Antiqua – Ars Nova – Ars Subtilior: Polyphony from the age of cathedral builders (1140-1440), Laus Polyphoniae 2025 told the story of how cathedrals became musical laboratories where the greatest composers and performers of their time created the sounds of the Middle Ages. The programme covered different periods of medieval music history: the ‘old style’, or ars antiqua, with its search for new ways of notating rhythms; ars nova, in which polyphony became ever richer and more complex; and ars subtilior, with its exquisite musical renderings of outstanding poetry. Alongside this sacred repertoire, the festival also explored the secular world of the troubadours and minnesingers. Laus Polyphoniae also focuses on young up-and-coming talent through the International Young Artist’s Presentation (IYAP), reviewed here, held on the first Saturday of the Festival.

The festival opened (Friday 22 August) in the extraordinary and recently restored 1872 neo-Gothic Handelsbeurs (the historic stock exchange) with the long-term festival favourites, the Huelgas Ensemble with their artistic director, Paul Van Nevel. Their programme Notre-Dame Paris 1200 was based on the groundbreaking musicians of Notre-Dame around the year 1200, who changed music history for good. The principal creation of these Parisian pioneers was ‘organum’: a technique in which several voices move simultaneously along their own melodic line, a radical change from monophonic music! Alongside famous pieces by Léonin and Pérotin, choirmasters at Notre-Dame were conducti and motets by anonymous composers.

The acoustic and atmosphere of the Handelsbeurs is about as far removed from Notre Dame as you can get. Having only arrived in Antwerp about an hour before this concert, I didn’t have time to read the detailed essay by Paul Van Nevel in the sumptuous programme book. That explained in detail his approach to performance, based on contemporary accounts and would have helped me understand his inclusion of copious ornamentation, elaborations and rhythmic flexibility. One of the most distinctive ornaments was frequent little upward whoops at the end of notes, an ornament I don’t recall having heard before. For a group renowned for its accurate intonation and pure tuning, all this came as a bit of a surprise.

Setting his singers up in a circle on a central stage, Paul Van Nevel did his usual trick of rotating his conducting position through 90 degrees at intervals during the concert, until he came full circle at the end. All the usual Huelgas singing excellence was there, but overlayering of what to me, with no prior warning, frankly sounded weird. I am not a musicologist or specialist in music of this early era, but I do wonder whether taking the comments of onlookers writing around 900 years ago as gospel is the best approach to 21st-century music making. But it certainly made it ‘interesting’.

They opened with an anonymous Laudes regiae, a royal tribute for Eastertide written in what was then a traditional note-against-note style with monophonic passage set against passages in 4ths and 5ths. Highlight moments came with the repeated Exaudi Christe! phrases, an elaborate Christus vincit sequence and a series of Amens towards the end (which reminded me of Arvo Pärt), the last of which was crowned by a very high treble voice.

The following Hec dies by Léonin was the first example of the new two-voice organum, the extended note values of the plainchant acting as the vox principalis with a more fluid, free-flowing upper vox organalis. At key textural moments, the two voices moved together, the vox principalis adopting the rhythmic complexity of the vox organalis in a manner referred to as clausulae. A more complex example of organum came with Pérotin’s extended (10 minute) Viderunt omnes, an extension of Léonin’s two-part organum into four parts. Similar clausulae, now in four parts, were so powerful that there are reports of hysteria and hallucinations amongst listeners of this piece!

The text of Viderunt omnes (All the ends of the earth have seen the salvation of our God) was particularly appriate for the Handelsbeurs, whose lower walls are covered with maps of the world.

The following daytime (Saturday 23 August) was filled with the six on-the-hour concerts of the International Young Artist’s Presentation, reviewed here. The first of the two evening concerts started in St.-Andrieskerk with PER-SONAT and their programme Orpheus’ Echo, a musical journey through the 10th, 11th and 12th centuries through versions of the story of Orpheus and Eurydice. Billed as “linking the mythical world of Orpheus to the innovations of the Carolingian Renaissance”, the music included “hypnotising melodies of laments, poetic odes and pioneering organa” drawn from manuscripts such as the 9th-century Musica Enchiriadis and the 11th-century Winchester Troparium and the only named composer, Petrus Abaelardus – heralding the dawn of a new musical era!

The five members of PER-SONAT (Tobie Miller, Sarah M. Newman, Karin Weston, vocals, Marc Lewon, vocals, Carolingian cithara, lute & citole, Sabine Lutzenberger, vocals, harp & artistic direction) appeared in various groupings, starting with two singers who started off-stage. To the accompaniment of frequently quite violent strumming on the cithara and citole, the singers negotiated the complex rhythmic and melodic complexities of the organum settings. One of several highlights was Sabine Lutzenberger singing Peter Abelard’s famous lament of David, Dolorum solatium – a similarly lengthy piece was Albi ne doleas. Although all the performers were excellent, I particularly liked the singing of Karin Weston, little knowing that I would hear a lot more of her on another day, singing with memor.

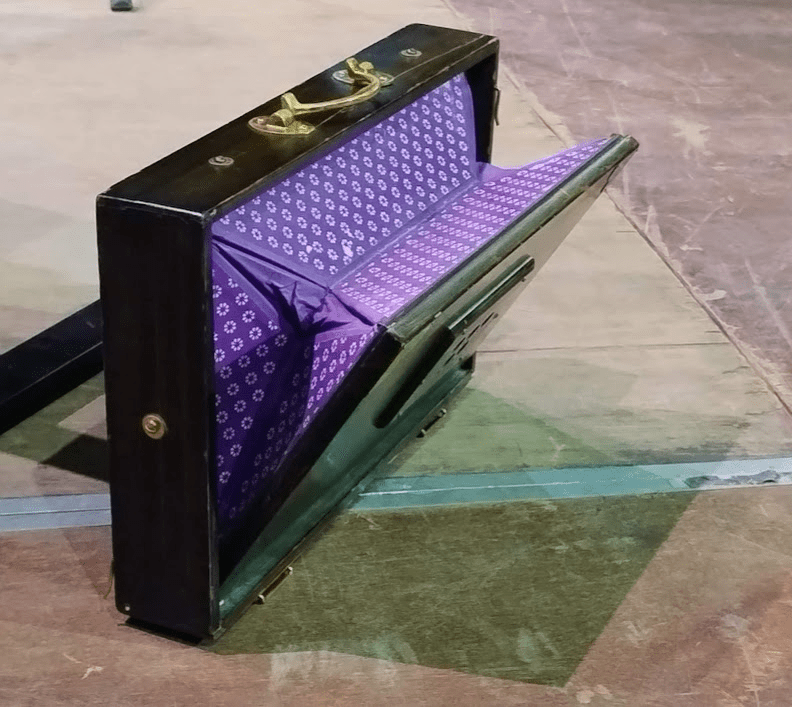

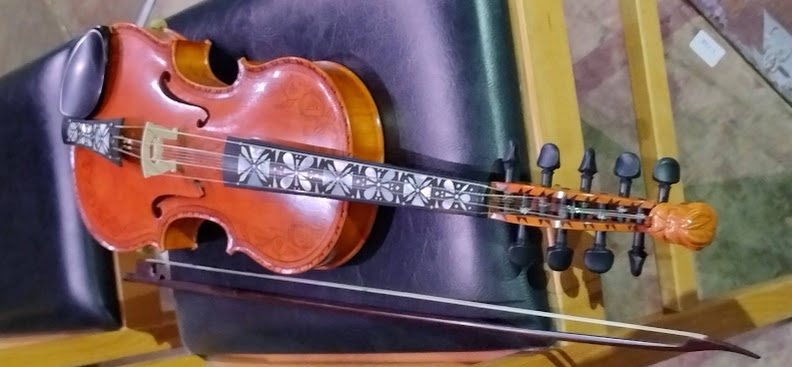

Lute, citole and the holly leaf shaped cithara

The late-night (22:15) concert in AMUZ was given by the Italian group Ensemble Micrologus with their programme recreating Adam de la Halle’s 1285 Le Jeu de Robin et Marion, which they termed the “first musical in history” and a “captivating 13th-century romcom featuring a shepherdess, her lover and an insistent knight”. Adam de la Halle wrote the work for Charles of Anjou’s court in Naples, where it apparently “went down an absolute storm”. As the concert description opined, “the ingredients are historical, but the story is perfect for our time: amorous drama, a touch of humour, sparks that fly… and a happy ending!”

This was a very professionally organised and presented concert. The ‘pastourelle’ combines folk melodies with refined polyphony in a way that bridges the gap between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance and combines elements of Ars Antique and Ars Nova, the latter in his polyphonic motets and rondeaus. The text is in Picard, a language spoken in Naples at the time by the nobles of the court, brought to Naples by Charles of Anjou. Alongside Adam de la Halle’s texts and music were pieces on the same theme by anonymous composers. Alongside the excellent singing was a wonderful range of instruments, including two impressive long trumpets, a bombard, bagpipes and several less prominent instruments. Over-eager applause conspired to give the show a false ending – the actual ending was a dance by all.

The performers were Enea Sorini, Andres Montilla, Giacomo Schiavo, vocals, Patrizia Bovi, vocals, harp & trumpet, Gabriele Russo, vielle & trumpet, Goffredo Degli Esposti, bombarde, flute, drum, transverse flute, double flute & bagpipes, Matteo Nardella, bagpipes, and Sara Maria Fantini, lute and citole. This video link shows extracts from Le Jeu de Robin et Marion as performed in Ravenna.

The two evening concerts on Sunday 24 August started with Mala Punica (Barbara Zanichelli, Beatrice Pellegrino, soprano, Marketa Cukrova, mezzo-soprano, Raffaele Giordani, Angelo Testori, tenor, José Manuel Navarro, Thomas Baeté, vielle, Gabriel Smallwood, chamber organ & clavicymbalum, Pedro Memelsdorff, recorder & artistic direction) with their programme reflecting the Passion and Patronage in the Motets of Johannes Ciconia: “A Franco-Flemish Polyphonist Conquers Italy”. Ciconia rose to international fame around 1390 when he moved from Liège to Rome. Crossing the boundary of the Ars Nova and the Italian Trecento, he created a new style and became the forerunner of five generations of Franco-Flemish polyphonists.

Their concert included motets and songs by Ciconia, two of the motets being isorhythmic, the other two non-isorhythmic. The songs included the ballad Merçe o morte (Mercy or death), sung by one of the two sopranos, accompanied by a fiddle and the gentle twang of a clavicymbalum. The sung text reflected a suffering lover wishing to die, but prevented from doing so by a woman who, nonetheless, will not return his affections. The use of repeated phrases throughout gave an additional impetus to the music. The noise of some of the performers moving to the back of the venue disrupted the mood – I could see no reason why the following piece was sung from behind the audience. Sadly, this wasn’t the only curious aspect of this concert.

Another disruptive event came towards the end when, again, the singers moved past the audience to the rear, for a piece that involved the few remaining on the stage and the rest at the back. The conductor stood awkwardly between the two, to the side of the audience, trying to conduct both groups of musicians. Which brings me on to the biggest distraction of the whole event – the bizarre antics of the conductor! Quite why such a modestly sized group needed anybody to conduct them is beyond me, particularly as for much of the time most, if not all, of them wouldn’t have been able to see the conductor. As was perhaps the intention, the people who did see the conductor were the audience, at least one of whom found his look-at-me antics most distracting. That said, the rest of the ensemble performed commendably well, seemingly not distracted by the conductor’s oddities. One instrumental change I would have

The second of the Sunday evening concerts was given by a group that I have followed almost since their foundation in1997, Trio Mediaeval (Anna Maria Friman, Linn Andrea Fuglseth, Jorunn Lovise Husan, vocals). Their programme Between Two Worlds: Hildegard von Bingen and the Messe de Tournai contrasted musical genres that would appear to be far apart – the mystic hymns of the 12th-century visionary abbess Hildegard von Bingen, the polyphonic Messe de Tournai, and a sequence of English anonymous Marian motets.

The Messe de Tournai is one of the oldest three-voice mass settings known to us. They were cobbled together around 1349 by a scribe who combined unrelated mass sections, three from the late 13th century and the rest from the Ars Nova era of the 14th century, to create one of the earliest polyphonic masses. The three anonymous Marian motets were found on parchment scrolls used to bind an English manor house building work account and moved, via Berkely Castle, to Oxford’s Bodleian Library and rediscovery in 1980. The extraordinary soaring melodies of Hildegard von Bingen are well known. They don’t fit any real musical genre or school, but stand apart – as, indeed, did Hildegard herself.

This ensemble remains loyal to the musical sources but adds contemporary touches, in this case with the use of square-section hand chimes to support the Hildegard pieces, a neat little squeeze box that produced the sort of sound that I imagine an organistrum might have produced and the haunting sound of a traditional Norwegian hardanger fiddle. Their singing is outstanding, with perfect intonation, unaffected pure tone,

Although the Laus Polyphoniae festival lasted the rest of the week, I was only able to stay until just after the lunchtime concert on 25 August. And it was a gem. The duo memor (Karin Weston, vocals, Elizabeth Sommers, vielle) gave a programme representing music for the construction of a cathedral: Congaudeat ecclesia! Cathedral of Sound.

The musical contribution of Notre-Dame, where the first three-voiced compositions in history rang out, and Gregorian melodies were enlaced with new voices to spectacular effect, is well known, and was the focus of several of the festival events. But memor explored beyond this repertoire with Cantica Nova music from the area around Paris and as far afield as Aquitaine and Sicily in the years around 1100. Consisting of highly ornamented and extended vocal pieces, these Cantica songs were far removed from the Notre Dame school. The music is daring and diverse, ranging from heavenly songs to the Virgin Mary to heartrending Passion music, and from exuberant songs of praise to scathing criticism of corruption in the Church. Memor paid tribute to these “musical dreamers who expanded the boundaries between liturgy and entertainment, devotion and liberation, earthly reality and panoramas of heaven”.

The only named composer was Philippus Cancellarius Parisiensis (Philip the Chancellor), the theologian, poet and Chancellor of Notre Dame who was represented by his Veritas veritatum and Clavus pungens. The interplay of voice and fiddle was exquisite, the presumably mostly improvised fiddle countermelodies from Elizabeth Sommers contrasting beautifully with the clear and focused voice of Karin Weston who had earlier excelled in the concert by Per Sonat.

Next year’s festival, Laus Polyphoniae 2026 is from Friday August 2026, with the title of “Polyphonic Europe circa 1600”. In the meantime, AMUZ continues with its year-round programme of concerts and events, details here.