Bach: Art of Fugue

Academy of Ancient Music, Concert Theatre Works

Laurence Cummings, Bill Barclay

Peter Bray, Steffan Cennydd, Imogen Frances, Simon Slater

Milton Court, 15 May 2025

Photo: Mark Allan

Johann Sebastian Bach’s Art of Fugue (Die Kunst der Fuge) is one of the greatest monuments of Western music. You mess with it at your peril. And mess with it at their peril is just what writer and director Bill Barclay with Concert Theatre Works did with the connivance of Lawrence Cummings and the Academy of Ancient Music (AAM), who commissioned this particular messing.

The Art of Fugue was composed during the last decade of Bach’s life, although the spurious accounts of Bach dying while composing the final fugue, on which much of the plot of this concert-theatre production relies, have long since been discredited. It was not published until shortly after Bach’s death, although autograph manuscripts of most of it survive. It consists of fourteen fugues (each called Contrapunctus) and four canons, all in D minor, and all using the same main theme, albeit in many varied forms. With the exception of the final fugue, which is written in conventional two-stave keyboard format, each piece has a separate line for each of the four voices (open-score) in a similar fashion to several learned musical works of the previous century or more. There is no indication of which instrument Bach intended or, indeed, if he intended it for performance at all, using it as an example of his skill in contrapuntal composition. There are no orchestral instruments of the time that could play all the lines on the same instrument, leading to the assumption that it was intended for the harpsichord. Performance on the organ is common, although there are many questions to be considered, not least the choice of registrations.

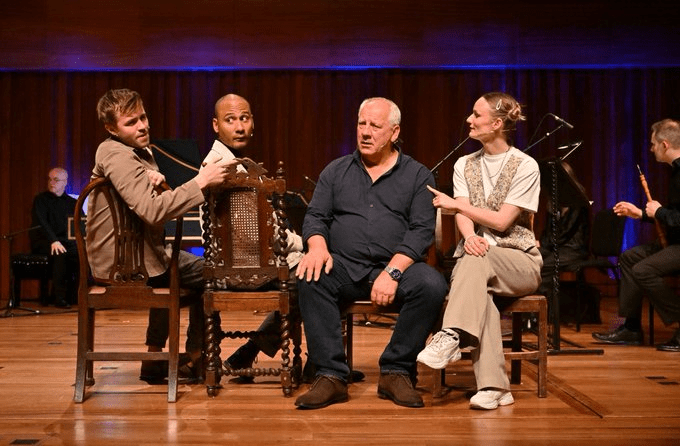

For this performance, two groups of musicians (a string quartet and three oboes and a bassoon) were grouped on either side of the central harpsichord, the whole ensemble enclosing the acting space. Promoted as “a completely new journey into Bach’s astonishing The Art of Fugue” through an “intimate, inquisitive piece of music theatre” where “Bach’s work and legacy springs to witty, touching, sometimes startling life, all illuminated by that astonishing music.” The four actors of Concert Theatre Works were given one goal: “to let us feel the living presence of music’s most beautiful mind”.

A pre-concert talk set the scene and exposed the potential difficulties of messing with Bach. Bill Barclay’s introduction, like his rather intense and obtuse programme note entitled “It’s All About You”, was very . . . how shall I put it? . . . American! He was “so lucky, so grateful, to be in this room . . . and to be alive”; and referenced the “Fourth State” of complete relaxation and bliss, as well as the “Flow State”. His programme essay references ranged from the Marx Brothers to Donald Tovey, with several mentions of class structure. Of course, wiith four absolutely equal voices, Bach’s Art of Fugue is the antithesis of any notion class structure, so it was presumably the actors who would explore class. Unfortunately, this initially happened through one actor, given the nerdy role of asking all the wrong questions to the condescending derision of the three others, having a stereotypical Welsh accent. The Concert Theatre Works website stated that “Four actors use scatological scenes to give hints to the audience as to how to listen to the next fugue”. I’m not sure if “scatological” was the correct word, but I struggled at times to see how each scene was referencing the following fugue. On more than one occasion, the task appeared to be too great, and an actor merely asked for another fugue!

The acted scenes combined various incidents in Bach’s life, including the move to Leipzig (with a suggestively spoken comment about the “gorgeous organs in Leipzig” – which was actually very far from the truth), the death of his first wife, the meeting with his second wife, and the inaccurate story of him dying while composing the final fugue. This saw the actor playing Bach collapse on stage and being helped off. This vaguely chronological sequence was very much at odds with the structure and sequence of the fugues. The music performed consisted of 12 of the 14 fugues together with a version of the organ choral prelude Wenn wir in höchsten Nöten sein. which was added at the end of the first publication to make up for the missing bars of the incomplete final fugue.

The instruments used alternated between the string and the wind quartet, although the solo harpsichord, played by Laurence Cummings, opened and closed the proceedings and played the central Contrpunctus X. Although there is no evidence for this, as an organist myself, and knowing Bach’s prowess, I have often wondered if Bach intended the organ as the prefered instrument. Organists of the time would have been used to playing from open score, the method of publishing used by several earlier organ composers. But on this occasion, my choice changed to a preference for solo harpsichord, helped by Laurence Cummings’ sensitively intuitive playing. The orchestral instrumentalists played well, but the difference in tone and volume between the four voices seemed to me to work against the notion of four independent voices. I was also unconvinced by the use of the harpsichord as a continuo instrument in several of the fugues.

Given the notion of the acted interludes acting as a clue as to the meaning of the following fugue, I guess that whatever I might have thought of the varying relevance of the scenarios to the following fugue, they were all more entertaining that trying to explain to a generally non-specialist audience the intricacies of invertable counterpoint, mirror fugues, inversion, retrograde, augmententation etc. And the show attracted a capacity audience in Milton Court, who applauded enthusiastically at the end. I did wonder if there were a few ‘plants’ in the audience trying to encourage audience laughter during the early stages of the evening.