‘Birch Tales‘

The Picardy Players, James Batty

Art Workers’ Guild, 19 October 2024

This fascinating “multi-sensory concert experience” from the Picardy Players ticked several boxes of musical and historical interest alongside the senses of sight, smell, taste and touch, represented by displays of birch bark, wafts of woodland smells, birch juice drinks from the bar, and a honey pastry and a little pendant tied to birch bark left for us on our seats – all explained in the brief programme note by linking them to the various tales that we were about to hear.

Those tales reflect the social world of medieval Kyivan Rus’ with ‘stories of love, heartbreak and everyday life’ based on personal letters written on strips of birch bark. More information on the birch bark letters can be found here and, in far more detail, here. Ten of these were set to music by James Batty inspired by Slavic folk music from Ukraine and Russia, and his own adventures with complex tuning systems based on microtonality and 31 notes per octave tuning.

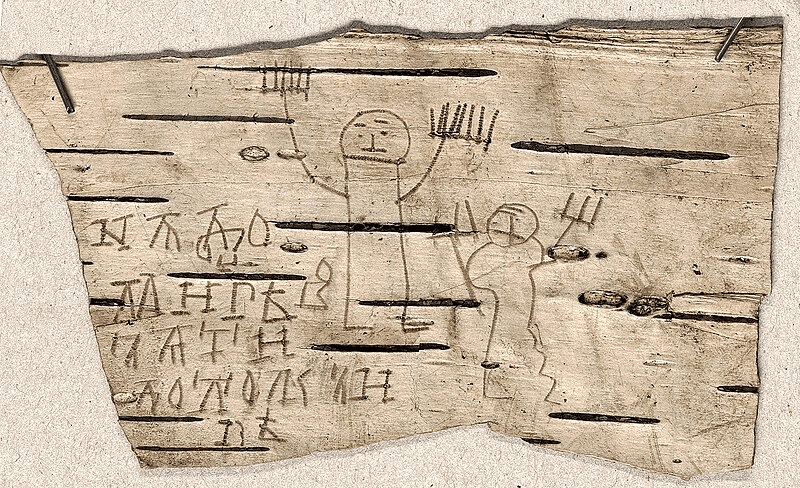

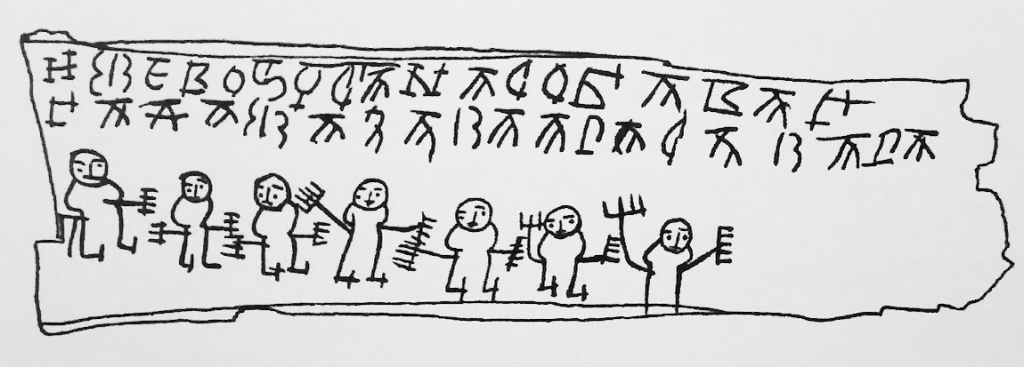

Birch-bark letter, mid-13th century. Spelling lessons and drawings

by a boy named Onfim, aged about 7.

The sequence of pieces based on the birch bark letters covered a range of stories and events from medieval Kyivan Rus’ starting with a script from a 6/7-year-old boy called Onfim (pictured above and below). The stories related included a woman who was stood up in a rye field (not for the first time), a mother reflecting on her daughter falling in love and marrying, a dressmaker cross with a jeweller for not supplying the required goods, a legal dispute arising from false accusations, a woman whose husband was leaving her and another whose husband was dying, both seeking help.

The songs were performed by four singers and six instrumentalists: Mariana Rodrigues soprano, Emma van der Scheer mezzo-soprano, Robert Folkes tenor, and Allyn Wu baritone; Madison Marshall and Elizabeth van ’t Voort, violas, Lizzie Knatt, Renaissance recorders, Philip Turner, lute, Oliver Wass, triple harp, and James Batty, harpsichord. They all combined for the first and last, un- birch-related pieces. Projected story lines helped us to follow the events depicted.

Script on a birch bowl

James Batty has recreated a 31-notes-per-octave system on a standard two-manual harpsichord, the playing of which involved occasionally playing on both manuals at the same time to find the required note and, presumably, different tunings in different octaves to add up to the 31 notes. More information can be found in this article from the Continuo Foundation who assisted in the funding of this event. Examples of recently constructed instruments using these tuning theories can be found in the Studio21 research project in Basel.

The birch bark songs were topped and tailed by two microtonal pieces, ancient and modern, both arranged by James Batty, starting with Nicola Vicentino’s Musica prisca caput (‘Ancient music has raised her head out of the darkness’). Vicentino (1511–1576) worked with microtonal intervals and built an archicembalo with 36 keys to the octave, its circulating meantone system producing, in effect, a pure intonation in all keys. This madrigal attempted to interpret ancient Greek musical theory using diatonic, chromatic and enharmonic scales. The concert finished with György Ligeti’s solo harpsichord Passacaglia ungherese arranged for the singers and instrumentalists of the Picardy Players. It can be heard in its original format here.

My understanding of the use of enharmonic keyboards in the Renaissance era was that they were intended to allow keyboard instruments to play in the mathematically pure intonation that singers could achieve. Examples of the Vicentino Musica prisca caput sung and played in this way can be found here sung by Exaudi and here played on a 24-tone archicembalo. They demonstrate this pure tuning. Despite the noticeable shifts from one tonality to another, the tuning is always pure on each chord, whatever ‘key’ it might be in at the time.

However, in this concert, it was the more unusual sounds of using microtones that dominated. I think this is very far from the original intention of the Renaissance composers who explored these tunings. They include Gesualdo’s intense compositions, which are thought to have been composed using an enharmonic keyboard.

I hope nobody came away from this event thinking that this is what ‘early music’ sounds like. It must have taken a lot of rehearsal for the impressive performers to get their tuning aligned to the 31 notes per octave of the harpsichord.