Laus Polyphoniae 2023

Antwerp. Townscape – Soundscape

Antwerp

18 – 22 August 2023

As the name implies, Antwerp’s annual Laus Polyphoniae festival is devoted to the music of the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance, a time when polyphony was paramount. Under the title of Antwerp: Townscape – Soundscape this year’s festival asked the question: “What did Antwerp sound like in the 15th and 16th centuries”? Alongside the shouting in the streets and markets and the dockland sounds, what music sounded in the churches and city palaces during Antwerp’s heyday?

Antwerp experienced an unprecedented economic and cultural boom in the late 15th and 16th centuries. The city was an international metropolis. Goods from all over the world were traded by merchant families who amassed large fortunes. Music was played in many places in the bustling city, from grand churches to private homes. The best singing masters were recruited to compose music for the liturgy. Publishers printed music for those who made music at home. Antwerp was also a centre of printing. Printers such as Phalesius and Plantin were renowned for the high quality of their music publications and surviving prints mean that music can still be performed. Several concerts during the festival were dedicated to these Antwerp music prints.

The festival opened on Friday 18th August in the spectacular Sint-Pauluskerk with festival regulars, the Huelgas Ensemble directed by Paul Van Nevel. They presented an anthology of music by 16th-century composers associated with Antwerp’s Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekerk, now the cathedral, then a major European musical focus. Motets and chansons by the likes of Noël Bauldeweyn, Ivo de Vento, Séverin Cornet, Andreas Pevernage, and Noé Faignient were interspersed with the sections of George de La Hèle’s Missa Fremuit spiritu Jesu. That was published in Antwerp by Christopher Plantin in 1578 and is based on the motet of the same name by Lassus. Although the composers are little known, the music was impressive, the varying moods reflecting the changing times and fortunes of Antwerp during this golden period. The opening pieces were low-key, for example, Bauldeweyn’s En douleur en trstesse and de Vento’s lugubrious Fried gib mir, Herr auf Erden. Cornet’s much more cheerful Cantantibus organis, a homage to St Cecilia, was followed by Pleurez musus, a lament by Pevernage on the death of the publisher Plantin. The concert finished, appropriately, with Antwerp’s answer to Lassus’s Innsbruck, ich muß dich lassen, Faignient’s Adieu Anvers. As is usual with Huelgas concerts, they performed in the round, circulating at intervals through 90 degrees to complete a full circle. It was partly the nature of the language of the music, but while vowels wandered around the vast space at will, consonants fared less well.

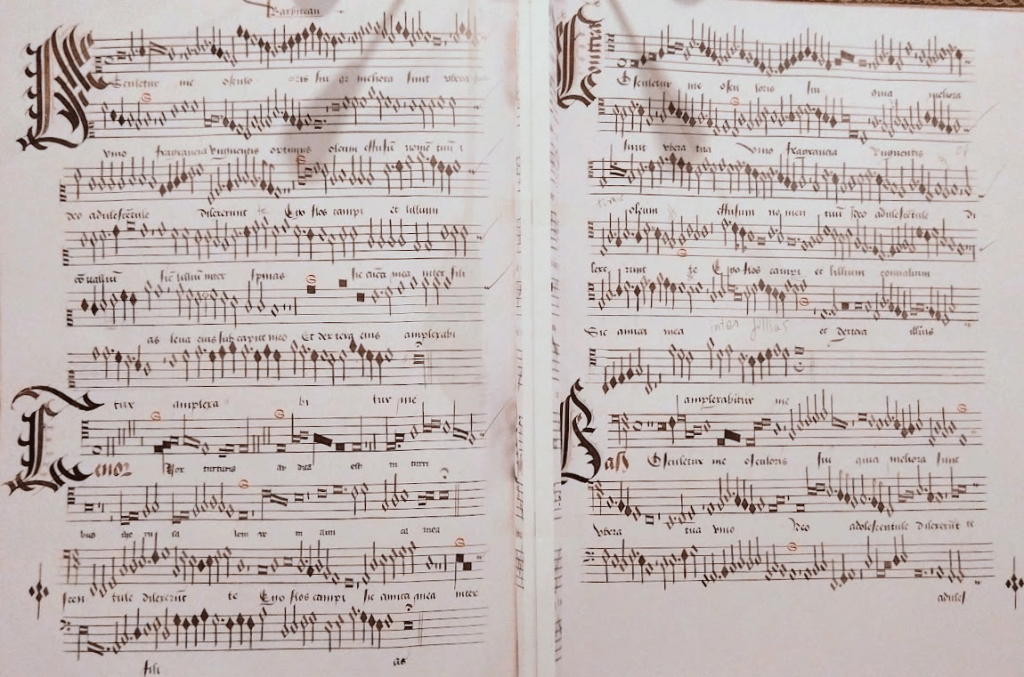

The daytime of the first Saturday of the festival is traditionally taken up by the International Young Artists Presentation (IYAP), a series of six concerts by young early music groups. More information and my review of these concerts are here. The evening concert was given by Cappella Pratensis, I Fedeli and Wim Diepenhorst, directed by Stratton Bull in the Sint-Pauluskerk. They recreated the procession and liturgy of one of the spectacular annual Confraternity of Our Lady celebrations for the Feast of the Assumption of Mary, with music from two of the leading Flemish representatives of late Middle Age and early Renaissance polyphony: Jacob Obrecht (1457-1505) and Jacobus Barbireau (1455-1491). Both were singing masters at the Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekerk in Antwerp. Obrecht was harmonically innovative and a pioneer in creating polyphonic textures around a chant melody, as demonstrated in his Missa Sub tuum praesidium. This was composed as an Easter Mass to impress Emperor Maximilian I but was also used for the Confraternity of Our Lady celebrations, conducted by Obrecht. The singers gathered around a copy of the 1507 partbook.

Jacobus Barbireau already enjoyed the respect of the emperor. The Osculetur me, based on the Song of Songs, is his only surviving four-part motet and was sung during this concert as part of the opening processional which stopped at Marian statues within the church. The processional sequence started with distant singing from just outside the main body of the church, but no indication of this had been given to the audience, many of whom continued talking and finding their seats. One feature of the concert was the contribution of organist Wim Diepenhorst improvising on the alternatim chants on a copy of a late 15th-century positive organ and an Apfelregal based on a 1506 woodcut (pictured).

The concert was preceded by a comprehensive talk by Prof. Jennifer Bloxam on the symbolism of the complex structure of Obrecht’s Missa Sub tuum praesidium and the Assumption rituals that formed the research for this concert. This was undertaken with the Alamire Foundation which enabled extended rehearsals and preparations. Key decisions had to be taken regarding missing text underlay and the use of instruments with singers, the latter aided by depictions of musicians in the art of the period.

If one Mass setting wasn’t enough for one evening, the Saturday late evening concert was given by the Boston-based Blue Heron, performing Ockeghem’s Missa Caput alongside music by some of the English composers whose music crossed the Channel, such as Walter Frye and Robert Morton. The programme reflected the strong cultural links between England and Antwerp. There were interesting comparisons to be made between the performing styles of this group with the Huelgas Ensemble and Cappella Pratensis heard in the earlier concerts. Whereas the earlier ensembles concentrated on detailed issues of consort singing, merging voices into the unified whole that polyphonic music seems to encourage, Blue Heron gave the impression of encouraging the opposite approach, making much of the individuality of individual voices that frequently came into prominence with no perceivable musical reason. This was aided by the different physical gestures and personal styles of the singers, some of whom seemed to be drawing attention to themselves and, occasionally, giving the impression of little tussles as to who was leading the group. It was usually possible to tell which singer was about to enter by these antics. One singer was particularly dominant in this respect, usually stepping back from the music desk when not actually singing, overusing gestures and often turning towards the audience in emphasis. Although the obvious solution for a listener was to close your eyes, there was also an effect on the music, with a lack of balance and consort between the voices that, to me at least, is pretty essential for polyphony.

The main evening concert on Sunday 20 August was given by the five singers of Utopia with their programme: Mirrors: Image motets from Antwerp. One of the themes of this year’s Laus Polyphoniae is the unique 16th-century Flemish engravings of Biblical scenes including polyphonic scores found in the Plantin-Moretus Museum. A key part of this concert saw ten such motets displayed on a large screen as they were sung, together with related visual commentaries and additional musical responses from composer and video artist Benjamien Lycke played on a chamber organ and the Apfelregal from the previous evening. This was part of the Mirrors project in the field of research and interpretation between AMUZ and the Museum Plantin-Moretus. The original engravings were available to view at the Plantin-Moretus Museum. The Mirrors sequence was preceded by motets by Agricola, Lassus, Turnhout, Cornet and Susato, generally in closely-wrought imitative counterpoint. Utopia demonstrated a very different musical and presentational style from Blue Heron, their matching suits and ties perhaps reinforcing an impressively coherent singing style with no dominant voices. They all sang from tablets, one aspect of which was the reflections from the screens under the stage lights which sent little patterns of light around the stage. As was often the case with concerts in the AMUZ concert hall, it was hot and humid making life tricky for performers and audience alike.

Blue Heron returned for the lunchtime concert on Monday 21 August with a programme based on Andreas Pevernage’s anthology Le rossignol musical des chansons, published by in Antwerp by Phalesius in 1597. Pevernage was Kapellmeister at the Cathedral of Our Lady in Antwerp from 1585 until his death in 1591. The concert also included music by other composers who had connections with Antwerp, such as Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck and Claude Le Jeune. They were joined by lutenist Paul O’Dette, his wonderfully undemonstrative performing style a welcome contrast to the extravagant look-at-me gestures of Blue Heron, as described in my earlier review. A couple of oddities from the audience started with one person who tried to start a round of applause at a couple of singularly inappropriate places, and a mobile phone that sounded at what was perhaps the most appropriate moment of the concert, with a song full of ‘la la las’.

The main Monday evening concert was given in St Paul’s Church by festival favourites, Stile Antico with their programme of music by Pedro Rimonte and Peter Philips. Rimonte (1565-1627) was a Spanish composer who was employed by Archdukes Albrecht and Isabella in Brussels. He was responsible for the court chapel and the chamber music. His music was published in Antwerp, including the magnificent Missa Ave virgo sanctissima, a five-part mass based on Guerrero’s motet of the same name. One of Rimonte’s colleagues was the English composer Peter Philips. He fled Anglican England because of his Catholic faith and settled in Antwerp in 1591. In 1597 he became court organist of the archdukes in Brussels. Rimonte is not a composer I was familiar with, but his music was impressive, contrasting imitative counterpoint with homophonic passages in a tightly unified texture. The sections of the mass were interspersed with some wonderful pieces by Peter Philips. Stile Antico is an extraordinary group, with 13 singers and no director, they stand in a circle with mixed voices, singing in perfect consort as if from one voice. Their encore of William Byrd’s ‘Retire my Soul’ was a touching conclusion to an excellent concert.

The Monday late-night concert took place in the Museum Plantin Moretus in the form of a musical narration by historian Michael Pye and virginal player Mario Sarrechia on Antwerp’s music during the late 16th-century, using the composer Susato as a thread. We heard how Antwerp broke the rules on an economic, religious, and intellectual level and how the music contributed to that ethos at a time when written keyboard music was replacing improvisation. Mario Sarrechia played a mother and child virginals, the child hidden in a drawer on the side of the mother which took a while to extricate.

The three concerts on Tuesday 22 August started at lunchtime in the AMUZ concert hall with Paul O’Dette playing music by the Antwerp lutenist, teacher and composer Emanuel Adriaenssen (1554-1604). He ran a lute school with his brother and performed for the well-to-do bourgeoisie to which he himself belonged. Many of the pieces in his Pratum musicum were arrangements for lute of vocal repertoire, French chansons, Italian madrigals, and Dutch songs. Copies were found in the libraries of Constantijn Huygens and King Johan IV of Portugal. This was a delightfully laid-back if rather lengthy concert that would perhaps have been better as one of the late-night events, not least to avoid the noise of distant hammering that could be heard through most of the concert.

The two evening concerts were given in St. Charles Borromeo’s Church by the Antwerp ensemble Graindelavoix. They were described as a “diptych of light and darkness” from the golden years to the fall of Antwerp, as reflected by the glory years to the fateful end of life in poverty of two Antwerp composers: Hubert Waelrant (1517-1595) and Séverin Cornet (1530-1582). Waelrant was a Franco-Flemish polyphonist who spent most of his life in Antwerp, working as a printer and a music teacher. Towards the end of his life, he was plagued by a lack of money. Cornet’s life followed a similar downward spiral. After training in Italy, he was employed as a singer in Antwerp and from 1572 until a year before his death was Kapellmeister at the Cathedral of Our Lady. The music of the first concert, Wonder Years, was based on the flamboyant experimental style of the 1550s and 1560s in Antwerp under the influence of Lassus, the Genoese, the Italian Academy in Antwerp, the music salon of the wealthy merchant and politician Cornelis Pruenen, patron of Waelrant and Cornet. Their Italian madrigals, Neapolitan songs, urban and occasional motets gloriously reflect the good times. The late-night concert reflected the darkness of the Hunger years with religious lamentations and madrigals reflecting the times of decline and oppression from the iconoclasm in 1566, the Spanish Fury, the Calvinist regime and the fall of Antwerp.

I got the impression that Graindelavoix prides itself on being unconventional and challenging to musical orthodoxy, judging by the lengthy essays by director Bjorn Schmelzer on their website and their performance style during this concert. They encourage an individual approach to concert dress and performing and singing style. They performed from a wide stage in the centre of the church, with the audience east and west of them. They had ten tall light stands each with an individual bulb hanging over the singers’ heads. The rest of the church lights were turned off, ending in darkness which made it impossible to read the tiny print of the programme book. The conductor had his own lighting control box by his side which he used to dim or turn off various lights as the group reformed. Unfortunately, the lighting control box had its own little lights which was a distraction. And, as all the singers used tablets (with the ‘interesting’ reflections mentioned in an earlier review, the lighting clearly wasn’t needed for them. They opened in processional style, the conductor, two archlutes and a cornettist arriving on stage first, followed during the first piece by the ten singers. In the rather anarchic staging, there was lots of moving about between and during pieces, with some singing straight to the audience while others retaining more of a consort formation. Either way, very few looked at the otherwise rather prominent conductor. Musically, the layout meant that there was little sense of consort, with some of the singers sounding very distant unless you were sitting right at the back and some voices dominated the sound. I was interested in their use of French ornaments for music that appeared to have no connection with French music

The festival continued until 27 August. The full programme can be seen here.