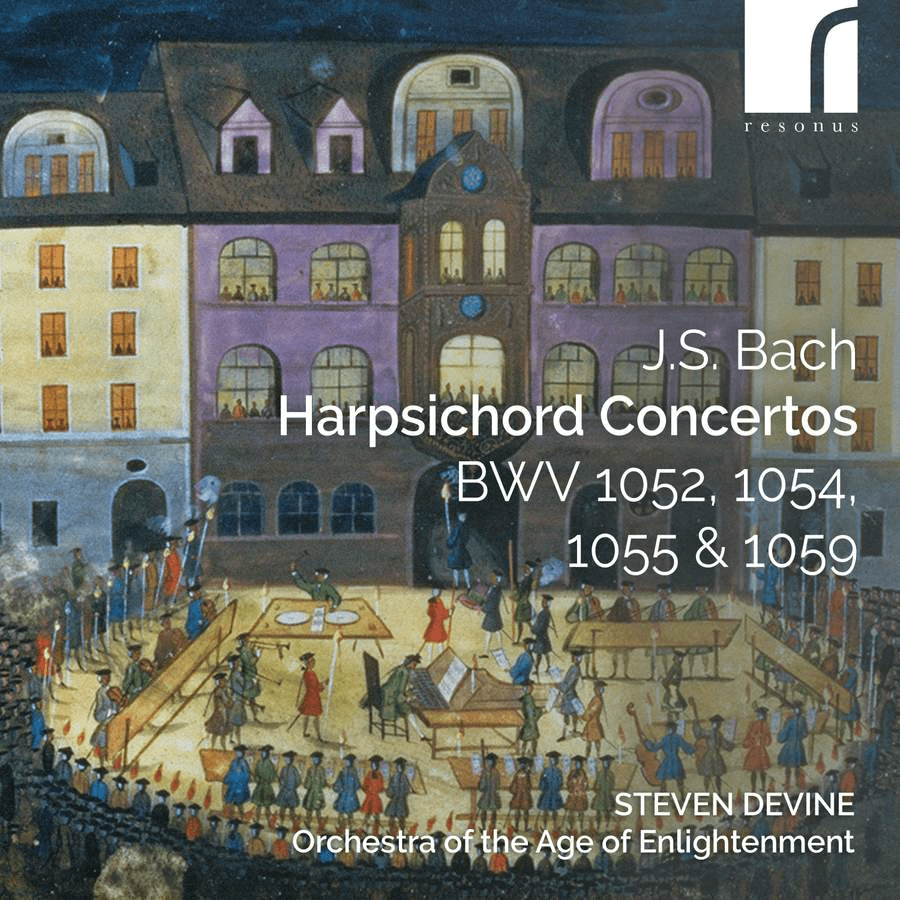

J S Bach: Harpsichord Concertos

BWV 1052, 1054, 1055 & 1059

Steven Devine, Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment

Resonus RES 10318. 63’30

This very welcome addition to the world of Bach recordings features three well-known harpsichord concertos plus what is, in effect, an entirely new concerto. Steven Devine’s programme essay sets out the often complicated history of the music played. The manuscript of these concertos is in Bach’s own hand. It contains seven concertos and nine bars of a D minor concerto, BWV 1059. There is strong evidence that only the first six concertos were intended as a set, with Bach’s traditional sign-off (Finis. S. D. Gl.) appearing at the end of the sixth concerto. The following BWV 1058 seems to have been an unsuccessful attempt at converting a violin concerto into a harpsichord concerto. The few bars of a D minor concerto (given the BWV number of 1059 despite its brevity) are of particular interest in this recording.

The nine bars that Bach notated are based on the opening sinfonia of the cantata Geist und Seele wird verwirret, BWV 35, with its exuberant obligato organ part. That sinfonia is probably based on an earlier instrumental concerto. Bach hints at his own playing or improvisation practice by notating additional twiddles to the BWV 35 score. For this recording, Steven Devine has reconstructed this D minor concerto, BWV 1059, based on music from the cantata BWV 35. The first movement continues with inspiration from the elaborations that Bach added to the solo line. The middle movement is based on the opening of the first aria of the cantata, leaving the solo organ line intact and giving the voice and other parts to an oboe. The final movement is based on the second Sinfonia of the cantata, with its solo organ line embellished with ornaments and flourished, some improvised and many finger-twisting.

It is up to Leipzig Bach Archive scholars to determine what BWV number (Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis: Bach works catalogue) this should be given. BWV 1059 is used in the recording information but, given there are only nine bars of BWV 1059, perhaps it should be labelled as BWV 1059sd – or BWV 35sd. Steven Devine certainly deserves credit for the reconstruction but, as yet, he doesn’t have a DWV catalogue.

Steven Devine’s approach to ornamentation and improvisatory flourishes are exemplary, neatly combining exuberance with respect for the score. His subtle use of rhetoric adds to the sometimes almost relentless nature of Bach’s keyboard writing. His treatment of Bach’s little hiatuses and moments of repose is impeccable, one delightfully timed example being the tiny Adagio near the end of BEV 1052iii. There is nothing that I can’t imagine Bach himself doing to the written score – as is the case with the reconstruction of whatever BWV number it should be.

The instrumentalists of the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment are Margaret Faultless & Kati Debretzeni violins, Max Mandel viola, Andrew Skidmore cello, Christine Sticher double bass, with Katharina Spreckelsen oboe added for the concluding BWV 1059. They provide excellent support to the harpsichord as well as excelling in their own often soloistic contributions.

The recording balance between the harpsichord and the other instruments is perfect, resisting the temptation to bring the harpsichord sound up to a higher level. If I had to find a potential criticism, it would be that the generous acoustic of St John’s, Smith Square has a greater reverberation than the likes of Zimmermann’s Coffee House (a possible venue for the early performances) where the largest room was apparently about 10x8m. Another point, which is perhaps a reviewer thing, is that I do prefer the commentary in the programme notes to follow the order of the pieces.